Bonhams announces New York Asia Week sale highlights for March 2021

© Bonhams 2001-2021

NEW YORK, NY.- An incredibly rare and museum-quality 11th century brass figure of Vajravarahi from Northeastern India, dating from the Pala Period; an important 10th century lacquered wood sculpture of Amida Buddha; and a wonderful grouping of Ming and Qing lacquer wares from the Collection of Robert W. Moore are among the highlights of Bonhams New York Asia Week sales announced today. This March, Bonhams New York will present a plethora of fine and rare works from a range of art historical periods throughout Asia’s past and present, the sales include: Chinese Works of Art and Paintings on Monday, March 15 at 10AM EST, Indian, Himalayan & Southeast Asian Art on Tuesday, March 16 at 6PM EST, and Fine Japanese and Korean Art on Wednesday, March 17 at 10AM EST.

Chinese Works of Art and Paintings

Monday, March 15, 2021

10AM EST

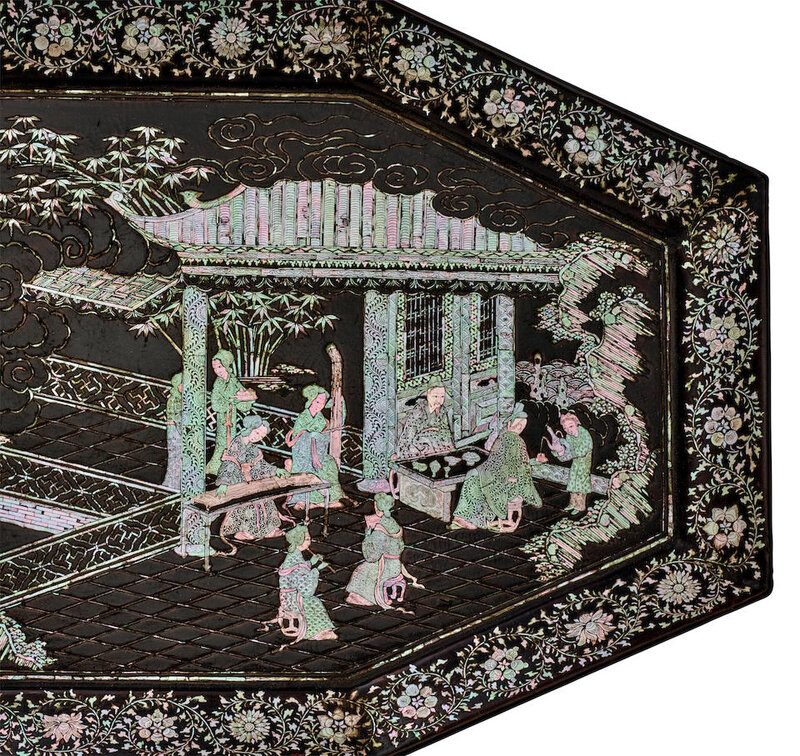

This sale offers treasured works of art from a series of prestigious private collections from America, led by the Ming and Qing lacquer wares from The Collection of Robert W. Moore, famed California collector of Chinese and Korean art. Among the highlights is a superb 15th/16th century Ming mother-of-pearl and black lacquer octagonal tray, exquisitely inlaid with courtly scene of figures at a lakeside pavilion (Estimate: US$25,000-35,000).

Lot 130. A magnificent mother-of-pearl inlaid black lacquer (bao luodian) octagonal oblong tray, Ming Dynasty, 15th-16th Century; 22 1/2 x 14in (57 x 35.5cm). Estimate US$ 25,000 - 35,000 (€ 20,000 - 29,000). © Bonhams 2001-2021

The center of the tray decorated in the Yuan style with a pavilion terrace scene with two gentlemen seated at a table whilst being served wine by an attendant and listening to female musicians alongside, all under the eaves of a pavilion on a fenced terrace surrounded by a lotus pond with a pair of mandarin ducks, rockwork, willow, bamboo and encroaching mist, the well decorated with a composite floral scroll of thirty-four flower-heads which is echoed on the exterior above small lappets.

L: For another octagonal dish dated to the second half of the 15th Century but also displaying certain Yuan characteristics such as the scrolling floral border with individual flower-heads and with the central scene of a gathering in a courtly setting, and very similar handling of drifting mist-clouds and striated rockwork, see James C. Y. Watt and Barbara Brennan Ford, East Asian Lacquer, The Florence and Herbert Irving Collection, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1991, pp.131-132, no. 58. See also ibid., pp.124-125, no. 54 and pp. 135-136, no. 60, the first, a Yuan dynasty nine-sided dish with similar border treatment, the second, a dish dated to the sixteenth century with elegant ladies with similarly-treated coiffered hair and facial features.

See Karamano, Imported Lacquerwork-Chinese, Korean and Ryukyuan (Okinawa), Selections From The Tokugawa Art Museum, No. 2,Nagoya, 1997, pp. 69-74, no's 125-135, for a group of Ming lacquer wares with similar courtly pavilions and figural scenes dated to the 15/16th Centuries. However an earlier tray with an almost identical border decoration bearing an added Huang-Qing (Ming era) painted mark but dated to the Yuan Dynasty does bear very close comparison. Indeed based on the border-decoration alone, both exterior and interior, a Yuan date for our tray would not be out of the question. However, the central design of our tray, and in particular the treatment of inlay and incised details, (rather more detailed and precise than the loosely-incised markings on the Yuan antecedent) found on the figures themselves, the clothing, architectural details and areas of rockwork, suggests a Ming dating, whilst still clearly in an overall Yuan style.

For other Yuan and early Ming dynasty dishes with similar courtly pavilion scenes and scrolling multi-flowerhead borders, see the Catalogue, Special Exhibition, Oriental Lacquer Arts, Tokyo National Museum, Tokyo, 1977, no. 492, for a circular dish (13 1/2 inches diam.) dated Yuan/early Ming Dynasty, from the Hakutsuru Art Museum, Hyogo; and also The Colors and Forms of Song and Yuan China, Featuring Lacquerwares, Ceramics and Metalwares, Nezu Institute of Fine Arts, Tokyo, 2004, no's 124-125, the latter box also octagonal in shape, a popular one during the Yuan dynasty. Another example, nine-sided, is illustrated by Denise Patry Leidy, Mother-of-Pearl, A Tradition in Asian Lacquer, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2006, pp.26-31, figs 22-24.

Other featured collections include:

• Select sculptures from The Estate of Marilynn B. Alsdorf, featuring a rare black stone cross-legged figure of Maitreya dating back to the Northern Wei Dynasty (Estimate: US$70,000-100,000).

Lot 79. A rare black stone figure of Maitreya, Northern Wei Dynasty, Longmen Caves, 5th-6th century; 17 1/4in (44cm) high. Estimate US$ 70,000 - 100,000 (€ 58,000 - 83,000). © Bonhams 2001-2021.

The slender figure depicted as an Indian prince, a tall crown rising above his smiling face with angular features, a flat necklace around his neck and a long scarf that falls downward from his narrow shoulders to frame the upper hem of his dhoti secured with a bow-tied sash, the sharply-cut folds of the material cascading across and around his pendant legs crossed at the ankles as he sits with his right hand raised palm-outward in a gesture of reassurance (abhayamudra) and his lowered left hand holding an object balanced on his knee.

Property from The Collection of James and Marilynn Alsdorf.

Provenance: C. T. Loo (Frank Caro, successor), New York, 22 September 1953.

Note: The Northern Wei dynasty was a period of political turbulence and intense social and cultural change. The messianic figure of Maitreya was believed to return to earth to preach the dharma once the teachings of the historical Buddha have been forgotten in those troubled times and to bring a new era of peace. The popularity of Maitreya among Buddhist patrons inspired arresting images in various poses. One format displays his right leg crossed over the left knee, the right arm raised with one hand touching the cheek of his head leaning slightly in the same direction, as documented in the stone Maitreya sold in our New York room, 19 March 2018, lot 8028. A second variation in the format has the figure of Maitreya with his pendant legs crossed at the ankles and his head leaning slightly downward to rest on the hand of his raised left arm: see the Maitreya of dark grey stone characteristic of the Longmen caves in Henan, dated to the early sixth century, from the collection of the Albright Knox Gallery sold at Sotheby's, New York, 19-20 March 2007, lot 503 (23 3/8 in. [59cm] high).

The third format, represented by the Alsdorf Maitreya, maintains the legs crossed at the ankles but the right had raised palm-outward in a gesture of reassurance. However there is some disagreement as to whether this pose is limited to Maitreya. Denise Patry Leidy discusses the problem in relation to two majestic painted sandstone images from late 5th century caves at Yungang, Shanxi: the larger image from Cave 25 (cat. no. 3a, 57 ½ in. [146.1 cm.] high) with a seated Amitabha Buddha to the front of his crown considered as probably the bodhisattva Guanyin, while the undecorated crown on the slightly smaller image possibly meant as Maitreya (cat. no. 3b 51 in. [129.5 cm.] high): see Denise Patry Leidy and Donna Strahan, Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2010, pp. 53-56. However a dark grey bodhisattva also in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (39.190, Fletcher Fund), with pose similar to the Alsdorf figure but seated between two lions, is considered as possibly Maitreya, datable to the early sixth century and probably from the Guyang cave site in the Longmen complex (see p. 169, cat. no A2).

For other sculptures of similar size and pose comparable to the Alsdorf figure, see the bodhisattva, identified as Maitreya, with his hand raised in abhayamudra (24 in. [61 cm.] high) from the Longmen complex acquired by the Art Museum of the University of Pennsylvania in 1940 from Yamanaka & Company: www.penn.museum/collections/object/208586. The site from which the relief was taken supposedly had a dedicatory inscription corresponding to 512. Also of note is the seated bodhisattva in the collection of the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco (B60S573, The Avery Brundage Collection, 22 ¾ in. [57.8cm] high), originally published by René-Yvon Lefebvre d'Argencé in Chinese, Korean and Japanese Sculpture in the Avery Brundage Collection, Tokyo, New York, and San Francisco, 1974, pp. 94-95, cat no. 35. However photographs now available on the website show both the thinness of relief and the reinforcement on the reverse of possible fragments, comparable to the Alsdorf sculpture and other examples, that occurred with their removal from the Longmen site in the early years of the 20th century.

• Ceramics from the 9th century through late Qing, led by a cream-glazed ingot-shaped pillow with an Imperial Qianlong inscription from The Rosalind Ching Pastor Collection (Estimate: US$50,000-70,000). Research suggests that it formed part of the renowned Japanese dealer Yamanaka & Co. Inc. property, which came to market in 1943 at the Parke-Bernet Galleries liquidation sale.

Lot 86. A rare imperially-inscribed white-glazed ingot-shaped pillow. The pillow Song Dynasty (960-1279), the inscribed poem dated 1746; 8 5/16in (21.2cm) across. Estimate US$ 50,000 - 70,000 (€ 41,000 - 66,000). © Bonhams 2001-2021.

The Cizhou-type pillow molded in two halves along its length, the join visible as a simple molded line that runs entirely around the pillow, the pottery washed with a cream slip and then covered in a lightly crackled glaze that thins and frits at the edges of the square ends and at a few points on the longer edges, one end with four kiln spur marks, one face very carefully and neatly engraved through the fragile glaze in clerical script with a one-hundred-character poem composed by the Qianlong Emperor and split into twelve eight-character lines and one four-character line followed by the inscription Qianlong Bingyin Yuzhi followed by two seals Qian and Long, some glaze staining.

Property from The Rosalind Ching Pastor Collection.

Provenance: Yamanaka & Company, Inc, Parke-Bernet Galleries, 1943, lot 715

The Rosalind Ching Pastor Collection, Chicago.

Exhibited: Art Institute of Chicago, Loan exhibition, 1997

Honolulu Academy of Arts, 2005.

Note: The sale of the entire stock from the three US. stores of Yamanaka & Company (New York, Boston and Chicago), was offered under the supervision of the Alien Property Custodian of the United States of America, during the Second World War. The item, illustrated as lot 715, was catalogued as a 'porcellanous pillow of Yu-yao ware bearing on one side an ode composed by the Emperor Ch'ien-lung. Length-8", Sung Dynasty'(See Figs.1-3).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

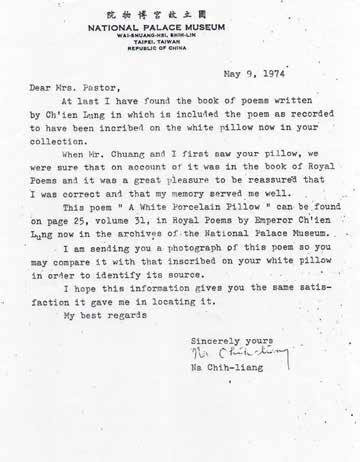

See also a letter (Fig.4) from the (then) Curator of Chinese Paintings at the National Palace Musum, Taipei, Na Chih-Liang to Rosalind Ching Pastor in 1974, with regard to the calligraphic poem on her pillow. This at least gives us a terminus ante quem for the pillow entering the Pastor collection.

Fig. 4.

In our poem, the Qianlong Emperor praises the beauty and fineness of the pillow, describing its whiteness ,shiny surface, and its jade-like strength and firmness and expressing his great admiration for the artistic sophistication that the Song artists achieved. More interestingly, perhaps, the emperor even imagined having conversations with ancient sages while sleeping on the pillow. The poem is followed by the Imperial designation and date.

The poem on our pillow reads:

枕石不如流,漱流不如石,瓷枕堅且潔,堪贈如茲客,既質玉之質,復白雪之白,磨涅不磷緇,

拂拭多光澤,恍挹神仙人,精神盍內積,豈伴窈窕女,粉黛汙顏色,可薦床之東,亦宜牖以北,

張氏榴應羞,錢家石豈特,虛堂夏午間,松濤泛幽席,竭此夢羲皇,古風如可即。

乾隆丙寅御題 「乾」、「隆」。

It is recorded in the Siku Quanshu, vol 31 (See Fig. 5).

Fig. 5 (SKQS Image).

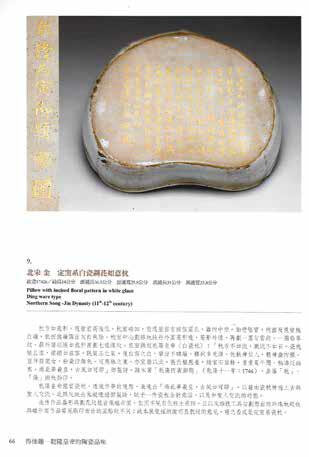

For another incised Ding-type pillow of oval shape in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, inscribed and gilt to the underside with the same Imperial Poem by the Qianlong Emperor dated to 1746 but written in a regular script rather than clerical script, see Peijin Yu, De jia qu: Qianlong huang di de tao ci pin wei - Obtaining Refined Enjoyment : The Qianlong Emperor's Taste in Ceramics , Taipei: National Palace Museum, 2012, p. 66-67, no. 9 (See Figs. 6-7). The same publication, pp. 162-163, no. 63, also illustrates a brown-glazed porcelain zither dated to the 18th century, which imitates the earlier lacquer versions from the Imperial collection, and which also bears a poem written by the Qianlong Emperor in 1746. This clearly demonstrates that poetic inscriptions inscribed on many items in the collection began early in the Qianlong reign despite the plethora of examples that date from the 1760's onwards.

Moreover, in an article published in Orientations, November-December 2011, pp.80-88, entitled 'Consummate Images: Emperor Qianlong's Vision of the 'Ideal' Kiln' by Yu Peichin, Curator at the Department of Antiquities, National Palace Museum, Taipei, the author notes that writing poems was a passion for the Qianlong Emperor. He was the most prolific of all the emperors in Chinese history, with over 40,000 imperial poems ascribed to him. Of these 190 are in praise of ceramics. He notes that Qianlong believed that ancient utensils could be used in everyday life and that he used early ceramics to commune with the ancient sages. Yu Peichin then references the poem 'The white ceramic pillow', 1746, (collected in Qinggaozong yuzhishiwenquanji [The Complete Collection of Imperial Poems by Emperor Ch'ien-lung], Taipei, 1976, ji 1, juan 31). This is the same poem written on our plain white ingot pillow and also on the underside of the florally decorated pillow in the National Palace Museum, Taipei (Figs. 6-7). He continues, that in the poem, the Qianlong emperor writes that by lying on the pillow, he can attempt to meet with the ancient leader Fuxi in his dreams, be close to his grace, and learn his style. As this poem reveals, not only did Qianlong view the ceramic pillow from the Northern Song dynasty as 'solid and clean' but that he may also have used it in his daily life. Yu Peichin then considers that in ordering the poem to be carved, he was actually imbuing the artifact with new meaning including the profound sense of communing with the ancient sages.

Fig. 6

Fig. 7

According to the author (citing records in the Palace Workshop Employment Archives of the Imperial Household Department (Neiwufu Zaobanchu gezuochengzuo huojiqingdang) there had to be direct instructions from the emperor before an order to carve each artifact was passed to the painting academy at Ruyiguan ('The Palace of Fulfilled Wishes') or Maoqindian ('The Hall of Great Diligence').

An ingot-shaped pillow (then called Yu-yao ware) of the Southern Song Dynasty is illustrated in Can jia Lundun Zhongguo yi shu guo jia zhan lan hui chu pin tu shou (Illustrated Catalogue of Chinese Government, Exhibits for the International Exhibition of Chinese Art in London, Vol. II. Porcelain), Shanghai, 1936, p.90, no. 101. It bears an Imperial Qianlong poem with the date 1765 (See Figs 8-9). The same pillow is also illustrated in the British publication Catalogue of the International Exhibition of Chinese Art, 1935-36, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1935, p. 125, no. 1284 (Lent by the Chinese Government). Interestingly, this pillow is now published as Qingbai ware, or 'blue-glazed' ware from Jingdezhen, rather than Yueyao from Zhejiang, see Peijin Yu, op. cit., pp. 64-65, fig. 8. Yet another ingot-shaped pillow, a pale-blue-glazed Jun ware example dated 1764, illustrated in the same National Palace Musem publication, pp. 142-143, no. 52, shows detailed images of the finely engraved clerical script, which highlights the dexterity of tool-work neccessary to engrave such a fragile porcellanous surface without causing damge, and bears very close comparison with the calligraphy on ours, in texture and quality.

Fig. 8

Fig. 9

The Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery have a near identical Cizhou-type white-glazed ingot-shaped pillow with a poem by the Qianlong Emperor, also of one-hundred-characters split into the same twelve vertical lines but cyclically dated to 1768. It is illustrated on the Smithsonian website, asia.si.edu/object/F1942.21. It is also illustrated by Chuimei Ho and Bennet Bronson, Splendors of China's Forbidden City, The Glorious Reign of Emperor Qianlong, The Field Museum, Chicago, 2004, p. 233, no. 293. Chapter VI entitled 'The Emperor as a Private Person' has various academic entries including one by Jan Stuart; 'Qianlong as a Collector of Ceramics'. Here she discusses the emperor's habit of adding his inscriptions and seals to not only paintings but also to jades, lacquers and ceramics. Using their pillow as an example she notes that the inscriptions give us an insight into his complexities as an art critic. In their poem, which is shorter but similar in content to ours, she states that the emperor starts with an art historical judgement, naming the pillow Ding ware. This is an understandable misidentification of this pristine white antique pillow. He then references two classical allusions to dreaming on pillows. At the heart of his text however is another allusion that takes the plainness of the ceramic as its greatest virtue and connects simplicity with human integrity.

Another Song dynasty ingot-shaped pillow (9 1/2 inches across) with a carved design (boys) under a greenish-white glaze is illustrated in Gugong Bowuyuan Cang Wenwu Zhenpin Quanji (Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum) Porcelain of the Song Dynasty (II), Hong Kong, 1996, p. 191, no. 173; whilst the earlier volume (I), ibid., p. 201, no. 182., illustrates an oval Cizhou pillow with carved peony decoration and a Qianlong Imperial poem with yuzhi mark and cyclical date of 1768.

• A select group of archaic jade ‘animal’ carvings from the Shang Dynasty through Han Dynasty from The Estate of Robert Youngman, including a russet jade Shang bear (Estimate: US$30,000-50,000).

Lot 9. An olive-green, beige and russet jade figure of a crouching bear, Shang Dynasty (circa. 1600-1100 BCE); 1 5/8in (4.2cm) high. Estimate US$ 30,000 - 50,000 (€ 25,000 - 41,000). © Bonhams 2001-2021

The bear seated on its rear haunches in a crouchi.ng position with forelegs resting on the knees of the drawn-in rear legs, the bear's large head with wide mouth resting on the forelegs, the eyes cut in low-relief below simple rounded ears, the rounded body cut with ridged channels of scrolls, a short hole drilled to the back of the head.

Property from the Estate of Robert P. Youngman

Provenance: Sotheby's, Hong Kong, The Robert Youngman Collection of Chinese Jade, 3 April 2019, lot 3419

Alvin Lo Oriental Art Ltd., New York.

Published: Robert P. Youngman, The Youngman Collection of Chinese Jades from the Neolithic to Qing, Chicago, 2008, pl. 32.

Note: For a very similar jade bear formerly in the Rafi Y. Mottahedeh Collection and dated to the Shang dynasty, see Sotheby's, New York, 4 November 1978, lot 162. Similarly positioned, it too had a small hole drilled to the back of the head. It had previously been published and exhibited at the Victoria and Albert Museum in the ground-breaking jade retrospective Chinese Jade Throughout the Ages May-June, 1975, p. 35, no. 44. It was also published by S.H. Hansford, Chinese Jade Carving, London and Bradford, 1950, pl. XXVa. and again in Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, 1973-74/1974-75, London, 1976, (a special edition for the Victoria and Albert Museum Exhibiton), p. 35, no. 44, where its owner is listed as Mr John M Crawford Jr.

Two jade bears from a Western Zhou Dynasty tomb of the Marquis of Jin and his wife in Shanxi province are illustrated in Zhongguo chutu yuqi quanji, vol. 3, pls. 125 and 126. See also a similar jade crouching bear from the M. Calmann Collection, Paris, illustrated in International Exhibition of Chinese Art, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1935-36, no. 283.

See the Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 1973/1974, Volume XXXII, No. 2 in an article by Maxwell Hearn and Wen Fong entitled 'The Arts of China, The Age of Ritual: The Shang Dynasty' for a depiction of a marble bear (4 1/2 inches high) in a very similar crouching pose, though devoid of surface decoration and dated to the 13th - 11th Century BCE (Illustration no. 7).

For a Shang dynasty buffalo also carved in the round, using a similar jade material and with related relief scroll decoration, see Max Loehr, Ancient Chinese Jades from the Grenville L. Winthrop Collection in the Fogg Art Museum, Harvard University, Massachusetts, 1975, p. 123, no. 148. Later in the same publication, a crouching bear is illustrated that entered the Collection in 1943 that is dated to 'probably' the Western Zhou period. It too bears close comparison.

For other small figural jade carvings of similar size, format and decoration, see China: 5,000 Years: Innovation and Transformation in the Arts, Guggenheim Museum, New York, 1998, p. 208, no. 10 (1 & 2) both unearthed in 1976 from Fu Hao tomb No. 5, Anyang, Henan province and now in the Henan Provincial Museum, Zhengzhou.

Highlights of Chinese paintings and calligraphy date from the 16th through 21st century, including:

• An interesting collaborative fan painting (Estimate: US$8,000-10,000) by two leading painters of the 19th century Shanghai School: Xugu (1823-1896) and Wu Changshuo (1844-1927). Created for their fellow artist of the school Ren Yi (1840-1896), this one small fan connects the three giants, and is a testament to the collaborative and social nature at play in Shanghai at the time.

Lot 186. Xugu (1823-1896) and Wu Changshuo (1844-1927), Rock and Bamboo, 1887. Round fan leaf, mounted for framing, ink and color on silk, signed by Wu Changshuo and Xugu, dated dinghai, with one seal reading Wu Changshuo yi shou chang; 9 3/4in(24.8cm) diameter. Estimate: US$ 8,000 - 10,000 (€ 6,600 - 8,300). © Bonhams 2001-2021

The inscription by Wu Changshuo indicates this collaborative work was created for Ren Yi (Ren Bonian, 1840-1895), a fellow Shanghai artist . Collaborative paintings, where two or more artists compose a single work, were popularly created among members of the late 19th century Shanghai School, and underscore the tight personal and professional connections.

Lot 223. Qi Baishi (1864-1957), Mice and Candlestick. Mounted for framing, ink and color on paper, inscribed with a dedication by the artist and signed Baishi, with one artist's seal, 40 x 13 1/2in (102 x 34cm). Estimate: US$70,000-90,000 (€ 58,000 - 74,000). © Bonhams 2001-2021

Provenance: Christie's London, 10 May 2016, lot 83

Collection of Hans J. Christensen (1922-1985).

Note: Hans J. Christensen (1922-1985) was a Secretary of the Royal Danish Legation in Beijing between 1952 & 1954. During this brief stint in Beijing, he developed an interest in Chinese art.

Indian, Himalayan & Southeast Asian Art

Tuesday, March 16, 2021

6PM EST

Leading Bonhams marquee sale week is a museum-quality brass figure of Vajravarahi from Northeastern India, dating from the Pala Period, circa 11th Century (Estimate: US$400,000-600,000). Possibly one of the earliest known bronze sculptures of Vajravarahi in existence, this figure from the eminent Nyingjei Lam Collection has been on loan to the Rubin Museum over the past 15 years, and has never since been published. Vajravarahi has been the most important female meditational deity in Tantric Buddhism since 11th century in Northeastern India, and it was at that very moment this figure was created. It brims with expressive iconography recalling the Indian myth of the Earth Goddess, envisioned as a young girl rising from the depths of cosmic waters. Bronzes remaining in India are believed to have been buried, but the alluring buttery patina on this figure suggests that it had been taken to – and preserved in – Tibet in the 11th or 12th century.

Lot 305. A brass figure of Vajravarahi, Northeastern India, Pala Period, circa 11th Century; 7 1/2 in. (19 cm) high. Himalayan Art Resources item no.16914. Estimate: US$400,000-600,000 (€ 330,000 - 490,000). © Bonhams 2001-2021

Provenance: Nyingjei Lam Collection, acquired in the 1990s.

Note: Dancing on a corpse representing the human ego, Vajravarahi is a form of the most important female meditational deity (yidam) in Tibetan Buddhism, providing a route to enlightenment. Aloft in her right hand she wields a flaying knife (kartika), which tantric practitioners use in rituals to visualize flaying their own limited self-perception. In her left hand she holds a skull cup (kapala). The staff (khatvanga) cast in the crook of her left arm is a visual cue to her male counterpart Samvara, another key yidam. Also known as a "transformative deity", a yidam serves as a transcendent role model, embodying a set of doctrines, meditations, and ritual practices that a tantric practitioner uses to transform their consciousness and be reborn instantly as the enlightened yidam itself. With her implements, garland of severed heads, and crown of dried skulls, Vajravarahi's terrific vision confronts our mortal limitations. Yet, she does so with the grace and beauty of a young dancer poised entirely on the ball of her left foot. She has a composed, deliberate manner. Underfoot, swirling vegetal waters of the cosmos have given rise to the lotus she dances upon, as more vines rise to support her—for Vajravarahi is the sacred, cultivated blossom of Buddhist wisdom.

Rich with such expressive iconography, this inspired bronze of the goddess derives from the cradle of Tantric Buddhism in Northeastern India. The sculpture is cast in the Pala style of the 11th century, coinciding with the period in which devotion to Vajravarahi and related yidams emerged as central practices in Tantric Buddhism as it would subsequently be preserved in Tibet. Thus, this refined bronze is likely among the earliest depictions of the goddess in bronze.

Vajravarahi is a form of Vajrayogini, the most important female yidam, with a porcine head protruding from the right side of her skull (ibid., "Vajrayogini"). In Buddhist teachings, the pig represents ignorance, one of the three primary obstacles to enlightenment. Thus, Vajravarahi's appearance alludes to her ability to confront and transform this poison into wisdom. There is a general scholarly consensus that Vajravarahi is an adaptation of the Hindu goddess Varahi, the female counterpart to the boar avatar of Vishnu, who raised the Earth from a cosmic watery abyss. The sculpture appears to evoke this heroic, divine act. Vedic literature frequently likens the Earth to a delicate young girl, embodied here by Vajravarahi, who is shown flowering out of chaotic vegetal waters represented by the scrollwork around the base.

Together with the band of plump lotus petals around the sculpture's base, the exuberant scrolls draw on an iconographic convention that permeates Indic religions. Transcending earth, water, air, fire, and space, the aquatic flower symbolizes the sacred source of the cosmos—its stem is life's umbilicus. In Buddhism, the image of the lotus arising from its murky bed is used as a metaphor for any sentient being's ability to achieve enlightenment, regardless of their karmic debt. Below Vajravarahi's right shin, a floral stem rises from the scrollwork and sprouts a wish-fulfilling gem, itself a microcosm of the sculpture's overall sentiment, conveying the promise of the transcendent boon Vajravarahi represents for practitioners.

While the petaled rim of a lotus pedestal supports almost any bronze sculpture of a Buddhist deity that survives with its base, the vines and waters below are much rarer. They are sometimes seen in stone sculpture from the Pala period, but seldom carried over into bronze figures. Examples in stone can be found on two 9th-century steles of Avalokiteshvara and a 10th-century stele of Varaha (Asher, Nalanda, Mumbai, 2015, pp.112, 113 & 117, nos. 5.15, 5.16 & 5.22). An 8th-century stone panel from Nalanda offers a precedent for the Vajravarahi's scrollwork in shallow relief (Chandra, Indian Sculpture, Washington, 1985, p.143, no.64). One reason for the rarity of depicting vegetal waters is that many Pala bronzes were cast separately from their original stands representing the subject, as one stand from the 12th century in the Metropolitan Museum of Art demonstrates (fg. 1 2009.21a–c). Bronze sculptural lotus mandalas also show the stem rising from water, such as a Vajratara mandala in the Indian Museum, Kolkata (Ray, Eastern Indian Bronzes, 1986, nos.281a & b). But, based on the few known examples, including two superlative bronzes from the 10th and 11th century of Buddha and Avalokiteshvara with large openwork roundels (Ray, ibid., nos.232 & 233), and a further 11th-/12th-century Manjushri sold at Sotheby's, New York, 24 March 2011, lot 26 (for over two million dollars) with similar shallow scrollwork, this added symbolism was reserved for outstanding castings.

Fig.1. Foliate Pedestal for a Buddhist Image, Late 12th century, India (probably Bengal). Partially gilded brass, copper base. H. 8 1/4 in. (21 cm); W. 7 1/4 in. (18.4 cm); D. 3 1/2 in. (8.9 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Purchase, The Manheim Foundation Inc. Gift and Rogers Fund, by exchange, 2009 (2009.21a–c).

The exceptional artist has embedded yet more symbolism into a technical detail of his creation. The waters brim with additional sprouts creeping over the sides of the lotus pedestal. The vines perform a structural function by supporting the figure, who would otherwise be connected to the base only by the weak point of the left foot. This technical knowhow was commonly employed by Pala artists, though rarely so elaborately. More often, long trailing scarfs or even a plain stem at the back were used as supports, as for a Hevajra in the Nyingjei Lam Collection (Weldon & Casey Singer, Sculptural Heritage of Tibet, London, 1999, p.21, fig.14). A later Tibetan copy of Vajrayogini in the Pala style shows a simple stem rising from the top of the base (HAR 57313), and another of Vajravarahi in the Metropolitan Museum of Art has a more elaborate support rising from the tail of a goose (2014.720.2). Yet, all pale in comparison to the creative vision and technical prowess exhibited by the variety of flowers reaching upward in celebration of this Vajravarahi.

The 10th, 11th, and 12th centuries saw a period of religious and artistic transfer between India and Tibet known as the Second Dissemination of Buddhism in Tibet. While many sculptures imitating the Pala style were produced in Tibet during and after the Second Dissemination, the nuance and depth of this Vajravarahi's symbolism indicate an original model from Northeastern India. Indeed, the confident display of the knot tying Vajravarahi's belt at the small of her back, the crisp pendants hanging from her necklace, and the lozenges in the bangle around her left wrist, representing human bone ornaments sometimes used in tantric rituals, evince the intricate bronze casting of the late Pala period. The insistence on figural plasticity in India's material culture is alive in the suppleness of her waist and hamstrings. Rather than sacrifice a convincing portrayal of her balance in order to merely accomplish the iconography of her dancing, as is often done in Tibetan copies (fig. 2.) the trajectory of sprouting flowers cater to an ideal representation of her pose. Moreover, whereas Indian religious art aims to entice the deity with a sensuous body to temporarily inhabit, a Tibetan icon's sacred energy is provided by consecrations lodged within it. Therefore, the absence of a consecration plate underneath the sculpture, or of any indication that it was ever meant to confine one, is another compelling indicator that the bronze is from Northeastern India.

Fig.2. Vajravarahi in a Wrathful Pose, 13th century, Central Tibet. Copper alloy with turquoise, silver, and colors. H. 8 3/4 in. (22.2 cm); W. 4 1/4 in. (10.8 cm); D. 3 3/8 in. (8.6 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Zimmerman Family Collection, Gift of the Zimmerman Family, 2014 (2014.720.2).

Helping to narrow the dating of the bronze to c.11th century, the flaying knife (kartika) in Vajravarahi's right hand appears to have an early shape that subsequently fluctuates by the 13th century. Cast unambiguously here as a curved dagger, it differs from the wider crescent blades and ever-shifting positions of the handle represented across several 13th-century thangkas compiled as HAR set no.3765 ("Vajrayogini: Early Paintings"). However, an earlier Kadam thangka attributed c.1100 (fig.3. HAR 35845) depicts a knife more akin to the dagger in the present bronze, and in equally exacting detail. A 12th-century Pala bronze of Vajravarahi preserved in the Potala Palace Collection, Lhasa, also shows her brandishing a curved dagger (von Schroeder, Buddhist Bronzes in Tibet, Vol.I, Hong Kong, 2001, no.94A), while its comparatively reductive ornamentation and posture suggest it is a later casting. An excellent stylistic comparison in stone from the early 11th century is a famous Pala stele of Hevajra in the Bangladesh National Museum (Huntington & Huntington, The Art of Ancient India, New York, 1999, p.399, fig.18.13). His flaming hair is similarly arranged into a fan-like coiffure above a crown of three dried skulls tied by a ribbon with upswept ends. His torque's pendants also appear modelled after tiger teeth, the long necklace that approaches his navel is made of strings of beads, and the severed heads he wears as a garland are similarly dwarfed by his size.

Fig.3. Vajravarahi, Tibet, Kadampa Tradition, Circa 1100. Ground Mineral Pigments on Cloth, 72 x 50 cm (28.75 x 20 Inches), Himalayan Art Resources no.35845. Image courtesy of Walter Arader, New York.

By the end of the 10th century in Northeastern India, a new class of tantras ascended in popularity, centered around yidams such as Hevajra and Vajravarahi (cf. Linrothe, Ruthless Compassion, London, 1999, p.324). Called Anuttarayoga Tantras, or "Highest Yoga Tantras", they and their icons spread to the Tibetan Plateau as central practices during the Second Dissemination. As most Pala sculptures that remained in India were lost or buried during the onslaught of Muslim invasions at the start of the 13th century—which leveled the region's Buddhist monasteries—this Vajravarahi's buttery, un-encrusted surface, and cold gold pigmentation almost certainly indicate that it travelled to Tibet as an agent of the Second Dissemination.

Among the highlights are also sculptures from the Siddharth K. Bhansali Collection and a grouping of South Indian Ganesha sculptures, as well as:

Lot 329. A copper alloy figure of Ganesha, Tamil Nadu, Chola period, 12th century; 13 3/4 in. (34.9 cm) high. Estimate: US$250,000-350,000 (€ 210,000 - 290,000). © Bonhams 2001-2021

Property from the Collection of Siddharth K. Bhansali.

Expressing his affinity for the beloved elephant-headed god, a confident artist has cast Ganesha with an emphatic childlike smile behind the long, sinuous trunk. The mischievous "Remover of Obstacles", Ganesha is worshipped to bless both the start and success of almost any undertaking. In Chola times, a bronze Ganesha was a part of every festival. This sculpture shows signs of ritual use and ablutions, left with a polished forest green trunk. Ganesha's round belly is another area frequently touched by devotees, and the cord draped over his right shoulder has been rubbed down to a faint impression across his stomach.

Compared to many more dwarfish renditions, this model of Ganesha boasts a tall physique and other artistic merits astutely explained by Dr. Pal:

"But for the minimal apparel consisting of a short loincloth, the god would be naked. His short, plump legs and feet clearly demonstrate his tender age, but the ample overhanging belly and the torso are of an adult. This [His] composite human body carries a naturalistically modelled elephant head with a gracefully swimming trunk scooping up the sweet from the left palm. The corresponding right hand delicately grasps his broken right tusk which he is about to hurl at the Moon, who mocked the roly-poly lad for his inordinate gluttony for sweets. The second pair of hands hold the elephant-goad (right) and the noose (left). Noteworthy are the prominent fan-like ears, reflecting the unknown artist's familiarity with the elephant.

"Lively and elegant with his chubby legs, a hanging rotund belly, but a well-proportioned torso, the bronze is a handsome representation of the 12th century, still revealing the creative impulse of the Chola sculptors. Comparable are bronzes at the Melaperumpallam temple dated to 1178 [Dehejia 1990 figs 87-88; so also Pal 2005, no.169d for a stylistically closely related example). The Bhansali bronze, however, is distinguished by its unusual combination of proportions in conceiving the body and the endearing manner in which the tip of the long, sinuous trunk is about to lift the sweetmeat off the palm."

Published : Pratapaditya Pal, The Elegant Image: Hindu, Buddhist and Jain Bronzes from the Indian Subcontinent in the Siddharth K. Bhansali Collection, New Orleans, 2011, pp.167-8, no.90.

Exhibited : The Elegant Image: Hindu, Buddhist and Jain Bronzes from the Indian Subcontinent in the Siddharth K. Bhansali Collection, New Orleans Museum of Art, 5 August - 23 October 2011.

Provenance : Collection of Siddharth K. Bhansali, New Orleans

Acquired in London between 1978-83.

Lot 309. A gilt copper alloy figure of Lokeshvara Padmapani, Nepal, 13th century; 9 3/8 in. (23.1 cm) high, Himalayan Art Resources item no.16915. Estimate: US$100,000-150,000 (€ 82,000 - 120,000). © Bonhams 2001-2021.

Avalokiteshvara, 'The Lord who Looks upon the World', offers a calm, benevolent gaze as his right hand adopts the gesture of granting wishes (varada mudra). The lotus at his left shoulder symbolizes every being's potential to achieve enlightenment despite their past flaws—just as the flower rises from murky waters. Avalokiteshvara is an enlightened being who eons ago pledged to postpone his departure from the cycle of death and rebirth, with all its inherent suffering, until he has helped every other sentient being escape it first. Thus, he is a paradigm of compassion that Mahayana Buddhist practitioners aspire to emulate.

Produced on a more intimate scale, this sculpture depicting Avalokiteshvara is a quintessential Newari standing bodhisattva, one of Himalayan art's signature icons. The Newars are an ethnic group from Nepal's Kathmandu Valley who have been transmitting their artistic expertise across generations and are renowned for being among the most accomplished artisans in Asia. Newars were frequently sought after for major artistic projects in Tibet, Mongolia, and China. There is perhaps no better hallmark of the grace and sensitivity with which the Newars cast Buddhist sculptures than their classic representation of the young and lithe standing bodhisattva, seen in this example from the 13th century. The leitmotif of the standing bodhisattva in a graceful pose, with a bare torso, supple waist, and sheer lower garment, traces back to the Gupta period (4th-6th century), India's cultural Golden Age. A famed standing Padmapani from Sarnath in the National Museum in New Delhi exemplifies this visual idiom, which the Newars perpetuated (cf. Across the Silk Road, Beijing, 2016, pp.160-1, no.70).

Stylistically, the tail ends of the ribbons used to fasten Avalokiteshvara's crown (samkhapatra), appearing above each ear, help date the sculpture to the 13th century. Vajracharya has attributed the 'Rubin Museum Durga' (fig.1; C2005.16.11) to this period because its ribbons are more prominent than in Newari sculptures produced before the 12th century, while being also simpler than those from the 14th century, which often display additional tassels (Vajracharya, Nepalese Seasons, New York, 2016, pp.25, 133 & 139). The Rubin Museum's masterpiece also shares the present sculpture's robust figural proportions and facial features—particularly an equally pronounced brow ridge. Other c.13th-century bronzes showing these features include an Uma Maheshvara in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, a Vishnu in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and a Vasudhara formerly in the Pan-Asian Collection (von Schroeder, Indo-Tibetan Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1981, pp.347-50, nos.89F, 90E & 91B, respectively).

Fig.1. Durga Killing the Buffalo Demon, 13th Century, Nepal. Gilt copper alloy, H 10 7/8 x W 13 1/8 x D 7 1/2 in., Rubin Museum of Art, C2005.16.11, HAR65433.

The 13th century marked the beginning of the enduring Malla dynasty, which reigned over the Kathmandu valley until the end of the 18th century. As Ian Alsop has summarized, "The Malla period in general was a period of overall political stability punctuated by internecine squabbles between the various principalities of the Nepal Valley. It was a time of considerable prosperity, nourished by the valley's fertility and by a lucrative trade with Tibet and India. It was also a time of great artistic activity, and Newar artists prospered through the patronage of the devout of the Kathmandu valley, the various noble houses there, and the wealthy lamas who eagerly sought the renowned Newar artists." (Alsop in van Alphen (ed.), Cast for Eternity, Antwerp, 2005, p.124).

Provenance: Doris Weiner Gallery, Madison Avenue, New York (label on base)

Private Californian Collection.

Lot 317. A gilt copper alloy and repoussé shrine of Manjuvajra, Nepal, 17th-18th century: 8 3/8 in. (21.3 cm) high, Himalayan Art Resources item no.16920. Estimate: US$130,000-180,000 (€ 110,000 - 150,000). © Bonhams 2001-2021.

This distinctive shrine invokes Manjuvajra, an esoteric form of Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Transcendent Wisdom. With three heads and six arms, he crosses his principal hands at the chest, embracing his consort Prajna, and signalling a perfect union of Wisdom and Compassion. Both male and female deities brandish long swords in their top right hands, creating a powerful image of their ability to dispel ignorance and delusion. Manjuvajra's remaining three arms hold a lotus, a bow, and an arrow, common attributes for wisdom deities.

Manjuvajra's physical appearance is described in the Nishpannayogavali ('Garland of Perfection Yoga'), a Vajrayana iconographical treatise from the Pala period. The earliest known sculptures of the deity date to the 11th/12th century: see two Pala examples preserved in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, including a black stone stele (57.51.6) and a small bronze figure (L.2017.31.1).

The shrine's pedestal has an ornate façade symbolizing Manjuvajra rising from the ocean of existence on the 'sun disc' of a lotus. A robust central stem bifurcates with vines encircling a pair of lions, which are often shown guarding the thrones of Buddhist deities. The formal depiction of both motifs can be traced back to the Pala art of medieval Northeastern India, testifying to Nepalese art's remarkable conservatism. For example, compare the treatment of the vines or the two outward-facing lions with their tails whipped over their backs with several Pala stone sculptures published in Huntington, Leaves from the Bodhi Tree, Dayton, 1990, nos.4, 6, 13, 15 & 36-8. Similar elements were incorporated into the base of a large gilt bronze Buddha from the Khasa Malla kingdom sold at Bonhams, New York, 19 March 2018, lot 3019.

A gilt bronze figure of Chakrasamvara, dated 1709, has a similar compact scale, crown type, and bangles (von Schroeder, Indo-Tibetan Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1981, p.386, no.105B). Elaborate flaming repoussé aureoles are common to Nepalese sculptures of the 17th and 18th century (ibid., pp.390-1, nos.107B-D). Also see a contemporaneous but smaller bronze of Manjuvajra with consort preserved in the Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena (Pal, Art from the Himalayas and China, New Haven, 2003, p.99, no.64).

Provenance: Ex-Private French Collection, 1980s.

Fine Japanese and Korean Art

Wednesday, March 17, 2021

10AM EST

The Fine Japanese and Korean Art sale is comprised of more than 180 Japanese and Korean lots, led by an important 10th century lacquered wood sculpture of Amida Buddha (Estimate: US$100,000-150,000). This Amida Buddha was created during the Heian period (764-1158), considered the first golden age of Buddhist sculpture in Japan. The distinctly Heian features – the soft lines, the voluminous body and limbs, and almost childlike appearance with gentle serene expressions – are considered as a native Japanese style.

Lot 562. An important lacquered wood figure of Amida Nyorai, Heian Period (792-1185), 12th century; 35 1/2in (90.2cm) high (figure only), 42 7/8in (109cm) high overall. Estimate US$ 100,000 - 150,000 (€ 82,000 - 120,000). © Bonhams 2001-2021.

During the tenth century, the cult of the Buddha Amida Nyorai, Lord of the Western Paradise, began to assume a central position in the religious life of Japan: Amida, no longer depicted as part of a vast celestial hierarchy, achieved iconographic preeminence and was typically shown with only a pair or a small group of attendant deities. A single prayer, Namu Amida Butsu (Hail to Amitabha Buddha), if uttered with total sincerity, became the sole requirement for salvation, a simple credo that appealed to courtier and peasant alike. Gorgeously colored and gilded paintings of the raigo, Amida's descent from the heavens to greet the soul of the dying believer, were commissioned in large numbers by aristocratic patrons. In sculpture, the deity's serene and otherworldly yet compassionate and accessible persona inspired a series of master sculptors of whom the best-known is Jocho (died 1057). The cult of Amida perhaps found its most extravagant expression in the Phoenix Hall of the Byodoin Temple at Uji, not far southeast of Kyoto, where the entire building is a vast recreation of the Western Paradise, with a seated figure of Amida by Jocho as its focal point.

The Byodoin Amida is about eight feet (2.4 meters) high, but sculptures at the three shaku (approx. three feet or one meter) scale seen here, were installed in numerous temples in the capital region and beyond, while still smaller figures were commissioned by the aristocracy for their private devotions. For later Heian instances of this well-known iconography and approximately the same size, compare standing figures in Kyushu National Museum (12th century, 96.8cm), https://emuseum.nich.go.jp/detail?langId=zh&webView=&content_base_id=100015&content_part_id=0&content_pict_id=0 and Hyogo Prefectural Museum of History, (dateable to 1170, 96.2cm), https://www.hyogo-c.ed.jp/~rekihaku-bo/historystation/exhibit-meihin/meihin09.html.

Mass-spectrometer radiocarbon analysis of a microsample from this lot, carried out by Dr. Armel Bouvier for CIRAM Corporation (Report # 1217-OA-85N, February 6, 2017), indicated that the timber was most likely cut between the end of the tenth and the middle of the twelfth century, when the cult of Amida was at its zenith.

Equally appealing is an important model of a celestial musician from the Horyuji temple (Estimate: US$35,000-50,000). This figure is believed to have been attached to the rim of an elaborate jeweled canopy of one of the three important statues in the Golden Hall of Horyuji Temple, Nara – Japan’s first UNESCO World Heritage site. The canopy has been erected since the hall’s reconstruction after a fire in 670.

Lot 561. A rare and important model of a celestial musician from the Horyuji temple, Asuka period (538-710), 7th century; 13 1/4in (33.6cm) high overall. Estimate US$ 35,000 - 50,000 (€ 29,000 - 41,000). © Bonhams 2001-2021.

Decorated in polychrome pigments, ink, and gesso over camphor wood, the figure carved from a single block, shown kneeling on a lotus platform holding a biwa (lute), framed by an elaborate floral nimbus, the lotus petals of the pedestal each individually carved and inserted into the core, the nimbus carved from a single sheet of camphor wood.

Note: The Kondo (Golden Hall) of Horyuji Temple near Nara, Japan's ancient capital, houses three important statues: the Shaka Triad, the Yakushi Nyorai, and the Amida Buddha, each of them placed under an elaborate jeweled canopy with tennin (Sanskrit: apsara, celestial musicians) attached to its rim. During recent restoration work the bore holes on the edges of the canopies that would have held the musicians in place were counted and it is currently estimated that there were 24 figures on each. This figure appears to have been part of a group that was attached to either the eastern or the central canopy, both of which were erected during reconstruction following a fire in 670. All the figures of Nara-period manufacture were carved from single blocks of cypress wood and decorated in ink, vermilion, cinnabar, red ochre, and malachite and, like the present lot, most of them carry instruments such as flutes, drums, cymbals, or biwa. For a similar example from the Horyuji group now in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art, see Mayuyama Junkichi, ed., Japanese Art in the West, Tokyo, Mayuyama, 1966, no. 1; and for another example still in the collection of Horyuji Temple, see Kurata Bunsaku, Horyu-ji: Temple of the Exalted Law, Early Buddhist Art from Japan, New York, Japan Society, 1981, cat. no. 12.

The sale’s Korean section features:

• An outstanding selection of ceramics from a private Japanese collection formed in the early 20th century, including an intricately carved white porcelain brush pot (Estimate: US$40,000-50,000) carved with symbols of longevity: deer, cranes, bamboo and pine.

Lot 690. A fine white porcelain brush holder, Joseon dynasty (1392-1897), 19th century; 6 1/8in (15.6cm) high. Estimate 40,000 - 50,000 (€ 33,000 - 41,000). Photo: Bonhams.

Cylindrical with a slightly recessed foot, finely carved in relief on the surface with a continuous frieze of the symbols of long life, including deer, cranes, bamboo, pine, rocks and, reishi fungus, covered in a transparent glaze with a slightly blue cast. With a wood tomobako storage box.

Note: For a similar brush pot, see National Museum of Korea, Joseon shidae moonbang jaegu (The Elegant Beauty of Joseon-Period Scholars' Studies), Seoul, 1992, pl. 356, pp. 121.

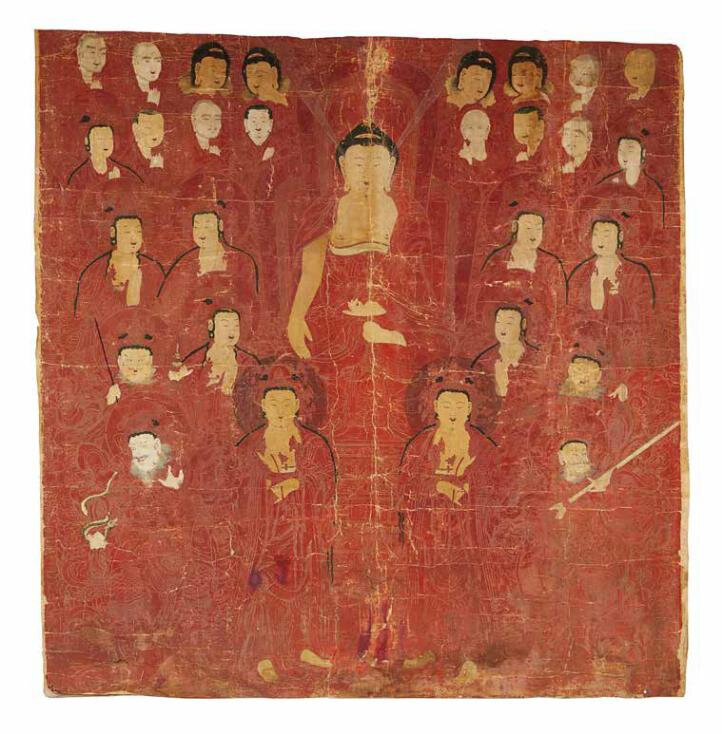

Lot 702. Anonymous, Yeongsan (Vulture Peak) Assembly, Joseon dynasty (1392-1897), 17th-18th century; 84 x 80in (213.3 x 203.2cm). Estimate: US$7,000-9,000 (€ 5,800 - 7,400).

A painting in ink, colors, gold, and silver on silk covered with a layer of vermilion pigment depicting Seokgamoni (the historical Buddha) preaching the Lotus Sutra to the Assembly on Yeongsan (Vulture Peak), surrounded by a hierarchical entourage of enlightened beings including bodhisattvas, disciples, guardian kings, and Buddhas of the past and future, Seokgamoni shown seated on a lotus throne, his right hand in the Hangma-chokji in (earth-touching mudra), rays of light emanating from his head, inscribed with a list of donors and the temple of origin, now effaced.

Property from the Collection of Paul and Elizabeth Colaianni.

Note: A large-scale Yeongsan Assembly painting such as this would typically have served as a backdrop to the arrays of Buddhist sculptural figures that dominated a Korean temple's Yeongsan Hall and would also have been an object of prayer and veneration in its own right. For a similar early example of this style of Yeongsan painting, executed on a red background, compare Treasure No. 1522 (designated July 13, 2007) in Dong-A University Museum, Seo-gu, Busan, dated 1565 (accessible on the Cultural Heritage Commission website, http://english.cha.go.kr).

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F56%2F88%2F119589%2F127649882_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F41%2F75%2F119589%2F126978834_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F08%2F51%2F119589%2F126856859_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F27%2F73%2F119589%2F125937937_o.jpg)