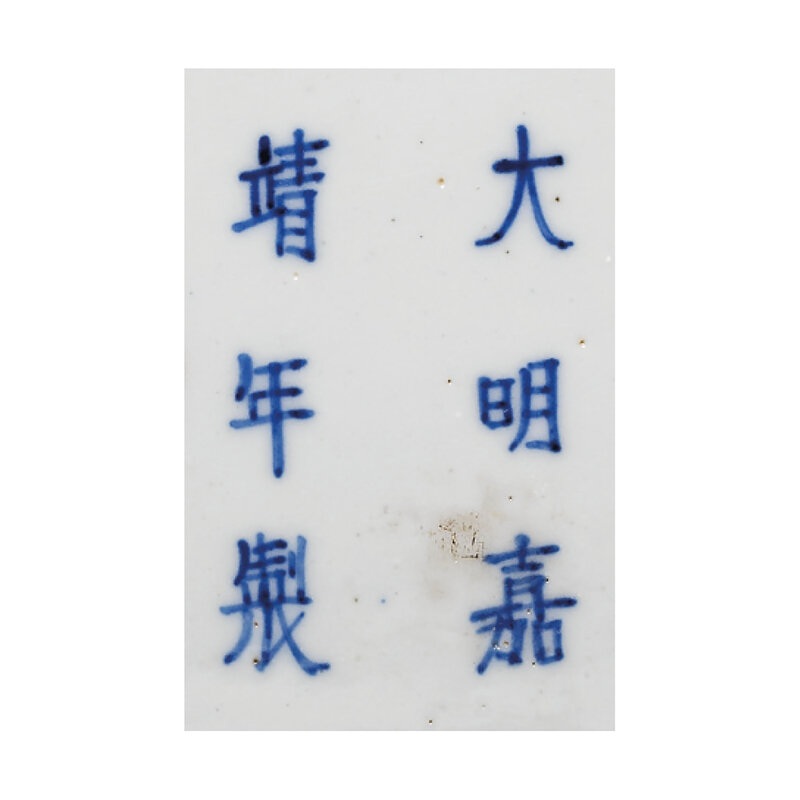

A fine magnificent and important blue and white 'boys' jar and cover, Jiajing six-character mark and of the period (1522-1566)

Lot 3007. A fine magnificent and important blue and white 'boys' jar and cover, Jiajing six-character mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1522-1566); 18 ½ in. (47 cm.) high including cover. Estimate On Request. Unsold. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019

The jar is exquisitely painted in underglaze blue of brilliant deep purplish tone on the high-shouldered body with a continuous scene of sixteen boys at various leisurely pursuits including one who is impersonating the school master, seated on a high-backed chair in front of a baby crawling towards a book; another boy pulling on strings attached to a toy cart on the ground, observed by his friend who is holding a large lotus leaf over the head of his companion riding a hobby-horse, in the further distance three boys are clustered around a square table and peering into a jar, probably containing fighting crickets, whilst another is riding on a cart, being towed by his friend, with two others who are acting as attendants, one holding a large fan and the other offering a potted plant, all within a terraced garden with plantains and pine trees, between overlapping lappets at the base and shaped panels enclosing fruit and floral sprays reserved on a wan-diaper ground on the shoulder. The cover is decorated on the sides with fruiting peach and lingzhi branches, the upper surface with trefoils enclosing radiating panels, below a bud-shaped finial with upright lappets below cash symbols and ruyi-heads, box.

Provenance: The Collection of J. M. Hu

J.M. Hu Family Collection, sold at Sotheby‘s New York, 30 November 1993, lot 238

The Collection of T. T. Tsui

The Jingguantang Collection, Important Chinese Ceramics and Jades From The Jingguantang Collection, sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 5 November 1997, lot 888

Sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 27 November 2007, lot 1738.

Literature: Christie's 20 Years in Hong Kong, Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art Highlights, Hong Kong, 2006, p. 97.

The Blessing of Many Sons

Rosemary Scott

Senior International Academic Consultant Asian Art

This magnificent jar, which is extremely rare, especially in having retained its lid, is one of a pair from the collection of the renowned Shanghainese collector J.M. Hu (1911-1995, Hu Jenmou, also known as Hu Huichun), whose studio name was Zande Lou (Studio of Transitory Enjoyment), and who donated a significant number of his monochrome porcelains to the Shanghai Museum. The current jar and its pair, along with other highlights from J. M. Hu’s collection, can be seen in a photograph taken in his Hong Kong residence in the 1980s (fig. 1). The current jar was sold at Sotheby’s New York in September 1993, and entered the Hong Kong Jingguantang collection belonging to T.T. Tsui (1941-2010), from where it was sold again at Christie’s Hong Kong in November 1997, before coming to auction again in November 2007. The pair to the current jar is now in the Hong Kong collection of the Tianminlou Foundation (fig. 2).

fig. 1 J. M. Hu at home, with the current jar on the left, circa 1960s

fig. 2 The pair to the current jar. A blue and white 'boys' jar and cover, Jiajing six-character mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1522-1566) in the Tianminlou Collection

Large jars of this type provide an ideal ‘canvas’ on which to depict one of the most lively and socially significant figural themes in the Chinese decorative arts – boy children playing in a garden. On the current jar this theme provides the main decoration encircling the jar and is painted in the rich jewel-like cobalt-blue, which is found on the finest imperial porcelains of the Jiajing reign. The desire for children, especially sons, was one which permeated all strata of society in traditional China. Families needed sons. In peasant families they were required to work the fields; among the scholar official class they could take up official posts, which would provide prosperity and security; while for the emperor they provided imperial successors. Thus, images of young boy children frequently appear in the Chinese arts, and rebuses were developed, which emphasised both the wish for many sons and grandsons, and the hope that those sons would be healthy, intelligent, honourable and successful. A daughter would move to her husband’s family when she married, but the filial piety required by Confucian teaching obliged a son to care for his parents in their old age, as well as to bring honour and prosperity to his family. Indeed, in traditional China sons were needed to carry out a range of ceremonies and rites for the benefit of family and ancestors.

In addition to the practical and Confucian need for sons, the importance of children in Chinese art also had roots in religious beliefs based in Buddhism, combined with some Daoist influence. Although not part of the Infinite Life Sutra (Sukhavativyuha Sutra, which was translated many times into Chinese, possibly the first being the 3rd century Da Amituofo jing), in Chinese Mahayanist Buddhism the re-born soul was believed to enter paradise as an infant. This may have been partly due to the influence of the Shangqing (Supreme Clarity) Daoist vision of the self in embryonic state. However, it appears to have been the Chinese Buddhist monk and philosopher, Zhidun (AD 314-366) who first described the re-born soul entering the Western Paradise (Sukhavati, the Pure Land Jingtu of Amitabha) through the calyx of a lotus flower.

One of the earliest painted images of a child on Chinese ceramics appears on a Tang dynasty 8th century ewer from the Changsha kilns, which is decorated with a young boy holding a lotus flower (illustrated by William Watson, Tang and Liao Ceramics, New York, 1984, fig. 95). The combination of a boy child and lotus is one of the most popular images, for it reflects the Buddhist belief in re-birth within a lotus, noted above, while simultaneously providing an auspicious rebus. One of the words for lotus in Chinese is lian, which is a homophone for lian meaning successive. A boy with the lotus thus suggests the successive birth of male children. This rebus appears on the current jar, on which one of the little boys can be seen holding a lotus leaf over the head of one of his companions, who is riding a hobby-horse. Interestingly, the way in which the lotus leaf is held on the current jar is reminiscent of the canopies that were traditionally held over the heads of those who enjoyed elevated social status – thus also suggesting a wish for high rank.

The ceramics of the Song dynasty saw a greater use of images of boy children in their decoration. While those which were carved or incised into the clay body, under the glaze, of vessels bearing both celadon and ‘white’ glazes tended to be of a generic and somewhat static type, those painted with a brush, underglaze, onto the surface of the body. were often depicted as full of life and charm – as are those on the current jar. Early examples of boys at play can be seen painted on the upper surface of Northern Song pillows made at the Cizhou kilns, such as the little boy fishing on a bean-shaped Cizhou pillow, and a boy playing football on an octagonal Cizhou pillow – both in the collection of the Hebei provincial Museum (illustrated in Zhongguo wenwu jinghua daquan – Taoci juan, Taibei, 1993, p. 302, nos. 443 (fig. 3) and 444, respectively).

fig. 3 A Cizhou pillow painted with a boy fishing. Northern Song ynasty. Collection of the Hebei Provincial Museum.

The theme of small boys playing was not restricted to ceramics, and paintings on silk depicting children at play found favour as early as the Southern Song dynasty. An artist famous for his paintings of children was Su Hanchen (fl. mid-12th century), who, under the Emperor Huizong (r. AD 1100-1126) of the Northern Song, was Painter-in-attendance at the imperial academy and, after the Song court was forced to flee south to Hangzhou, resumed his position at the Southern Song academy. Those of his paintings which have survived into the present day include Children Playing in an Autumn Garden (fig. 4) and Winter Play, both preserved in the National Palace Museum, Taipei (illustrated in A. Barratt Wicks (ed.), Children in Chinese Art, Honolulu, 2002, pls. 6 and 7, respectively), and Children Playing with a Balance Toy in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (illustrated in Tales from the Land of Dragons – 1,000 Years of Chinese Painting, Boston, 1997, p. 154, no. 26). Such paintings continued to inspire designs on the decorative arts from that time onwards. Su Hanchen tended to depict the children within garden settings, which emphasised the domestic nature of the scenes. It is probably no coincidence that when children came to be painted on Jingdezhen porcelain in the Ming period, these scenes were almost invariably set in luxurious gardens fenced with elegant balustrades – as on this Jiajing jar.

fig. 4 Children Playing in an Autumn Garden by Su Hanchen. (fl. mid-12th century), Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Although the theme of groups of children at play does not seem to have been much employed on ceramics in the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) or in the early Ming reign of the Hongwu emperor (1368-98), it does appear on rare, porcelain bowls of the Yongle reign (1403-24). A bowl of this type is in the Tianminlou collection, decorated with sixteen boys playing in a garden, illustrated in Chinese Porcelain - The S.C. Ko Tianminlou Collection, Hong Kong, 1987, p. 43, no. 15. (fig. 5) A Xuande mark and of the period (AD 1426-35) shallow, wide-mouthed, bowl with similar decorative theme is in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, and is illustrated in Catalogue of the Special Exhibition of Selected Hsüan-te Imperial Porcelains of the Ming Dynasty, Taipei, 1998, no. 152. On the Xuande bowl, although the boys are shown within a balustraded garden, mountains can be seen in the distance beyond the fence. However, after the mid-15th century the emphasis was clearly focussed on the garden itself and generally only clouds appear in the distance.

fig. 5 A blue and white ‘boys’ bowl, Yongle period. Tianminlou Collection.

The theme of boys playing in a garden really established its popularity in the porcelains of the Chenghua reign – both those decorated in underglaze blue and those decorated in doucai style. Blue and white bowls in several sizes and decorated with slightly different versions of the boys at play design were excavated from the late Chenghua stratum at Jingdezhen. Two of the smaller sized bowls are illustrated in A Legacy of Chenghua – Imperial Porcelain of the Chenghua Reign Excavated from Zhushan, Jingdezhen, Hong Kong, 1993, p. 234, no. C72 and C73) (fig. 6), while a significantly larger blue and white bowl decorated with boys at play in a garden is illustrated in The Emperor’s broken china – Reconstructing Chenghua porcelain, London, 1995, pp. 50 and 52-3, no. 54). A Chenghua blue and white, medium sized, bowl decorated with boys at play is in the collection of Sir Percival David (illustrated by Rosemary Scott in Elegant Form and Harmonious Decoration – Four Dynasties of Jingdezhen Porcelain, London, 1992, p. 56, no. 47), while ten similar bowls are included among the imperial treasures depicted on a long handscroll, dated to the 6th year of the Yongzheng reign (equivalent to 1728), entitled Guwan tu Pictures of Ancient Playthings, also in Sir Percival David’s collection. A Chenghua doucai cup with boys at play was also excavated from the late Chenghua stratum at Jingdezhen and illustrated in A Legacy of Chenghua – Imperial Porcelain of the Chenghua Reign Excavated from Zhushan, Jingdeezhen, op. cit., p. 268, no. C90. A pair of Chenghua doucai cups decorated with boys at play preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing, from the Qing Court Collection, is illustrated in Porcelains in Polychrome and Contrasting Colours, The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, vol. 38, Hong Kong, 1999, p. 194, no. 176.

fig. 6 A blue and white ‘boys’ bowl, Chenghua period. Collection of the Jingdezhen Ceramics Institute.

However, it was in the 16th century that porcelains decorated with designs of boys at play – executed in rich cobalt blue reached their apogee, and the most impressive of these are the large jars dating to the Jiajing reign (1552-66), as exemplified by the current jar. These jars are sometimes called ‘hundred boys jars’, and are especially skilfully painted in the finest cobalt. Not only does the greater size of the vessels provide the ceramic decorator with the larger ‘canvas’ and greater freedom in the portrayal of his subject, but the cobalt available at the imperial kilns in the Jiajing reign produced an exceptionally vibrant blue and greatly enhanced the decoration. The Jiajing reign was one during which the emperor was a devout Daoist, who became involved with alchemical Daoism. As his reign progressed, he became obsessed with two things – immortality and imperial sons. According to the Ming Shi (History of the Ming), in the 11th year of the Jiaijing reign (AD 1532) the emperor commanded that a Daoist ritual be held in the Imperial Garden with the specific purpose of praying for the birth of imperial sons. It was to be expected that the emperor’s desire for sons should be translated into designs on imperial decorative arts, including porcelains.

It is interesting to note that Ming dynasty bowls decorated with boys at play were included in the 1728 handscroll painted for the Yongzheng emperor, since this theme was clearly one which was still popular and important at the Qing court of the 18th century. In fact, the theme of boys at play reached a further peak of popularity in the Qianlong reign. The emperor’s fondness for this decorative theme is emphasised by the existence of a beautiful tieluo mural painted by the court painter Wang Youxue, who was a disciple of the European Jesuit artist Castiglione (Lang Shining), and others on the 28th day of the 2nd month in 1776 (illustrated in A Lofty Retreat from the Red Dust: The Secret Garden of Emperor Qianlong, Hong Kong, 2012, pp. 170-5, no. 33). (fig. 7) This mural is on the west wall of the central room of the Yanghe Jingshe (Supreme Chamber for Cultivating Harmony), which is in the Qianlong Emperor’s gardens in the Forbidden City, Beijing. The painting is one of several trompe d’oeil murals created in the palace which cover a whole wall and appear to extend the room, and in this case offer a view into a garden beyond. The focus of the scene is a group of eight imperial children at play, accompanied by two imperial concubines, while two more boys are depicted in the garden itself. The depiction of the young princes has strong similarities with the boys on the current jar.

fig. 7 Mural by Wang Youxue and others (1776) on the west wall of the central room of the Yanghe Jingshe, Forbidden City, Beijing.

Another rendering of young boys playing amongst flowers, rocks and trees, dating to the Qianlong reign, is a hanging scroll in ink and colour on paper entitled Children Playing in the Garden by the court artist Jin Tingbiao (active 1757-1767) preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing (illustrated in Forbidden City: Imperial Treasures from the Palace Museum, Beijing, Virginia, 2014, pp. 158-159, no. 109 (fig. 8). This painting depicts the boys at play, but also collecting seasonal flowers and herbs, and bears an inscription ‘Respectfully painted by your servant Jin Tingbiao’, and a poem by the Qianlong Emperor, dating it to a summer’s day in the jiashen year, equivalent to AD 1764.

fig. 8 Children Playing in the Garden by Jin Tingbiao (active 1757-1767). Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing

The boy holding a lotus leaf over his companion’s head, as noted above, suggests the successive birth of sons, and could also suggest ‘may my descendants live in harmony’ zisun hehe, because another word for lotus is he, which is a rebus for he和meaning harmony. The little boy over whose head the lotus leaf is held is shown riding a hobby-horse, which may be seen as a child’s version of the rebus ‘on top of a horse’ mashang, which in Chinese also has the meaning of ‘soon’ or ‘immediately’, suggesting the imminent arrival of a boy child. There are several other rebuses and wishes included in the design. Another of the boys on the jar carries an instrument called a sheng which provides a rebus for giving birth sheng and thus also provides a wish for sons. Interestingly, on this jar there appears to be a branch inserted into the pipes of the sheng. It is possible that this is intended to represent osmanthus (guihua), in which case these symbols combine to represent the phrase ‘continuous birth of noble sons’ (liansheng guizi), while the osmanthus branch may also be a reference to the Chinese saying huakai jiezi ‘blossoming flowers soon bear fruit’, which suggests abundant sons and grandsons as well as longevity.

Although it is not possible to see what is in the bowl into which the three boys seated at the table are peering. There are two likely references. It is possible that they are playing dice. In Chinese die are shaizi, which is a pun for shengzi ‘to give birth to sons’. The alternative interpretation of the scene is that the boys are playing with katydids (crickets). This interpretation would also relate to the birth of sons. The word for katydid in Chinese is guoguo, while the term for younger brother is gege, and so the combination of a boy with a katydid suggests the phrase jiao gege ‘calling for a brother’. Another of the boys on the jar is pulling an elaborate toy boat along with a length of string. In this case the boat, which is chuan 船in Chinese and provides a rebus for chuan meaning to pass on something, such as rank, from one generation to another. A further clue to the desire for a son to achieve rank, or indeed to succeed his father as emperor, is the boy seated on a four-wheeled cart, which is being pulled along by another child. The boy seated on the cart appears to be wearing a type of diadem – symbolic of royalty – while a third child holds a fan over his head, suggesting rank.

Both rank and intelligence are suggested by the group of children in front of the screen. The child seated in front of the elaborate screen, on which is painted a landscape, is clearly imitating an adult official, while another boy, seated to his right, is reading a book to suggest a studious temperament. The child on his knees on the ground appears to be crawling towards a book. This may be a reference to the tradition of offering a range of objects to a one-year-old child to see which items he will be attracted to. If the child reaches for a book, then it is assumed that he will prove a good scholar. This tradition of offering a range of things to a baby is still sometimes followed, and it is said that the 20th century scholar Qian Zhongshu (1910-1998) was re-named for the fact that he reached out and grasped a book on the occasion of his one-year celebration. His given name Zhongshu means ‘fond of books’.

On the shoulders of the jar are cartouches containing fruiting sprays – including peaches, symbolic of longevity. The cartouches are reserved against a band of wan卍lattice, multiplying the good wishes 10,000 times, while each section of lattice also bears an auspicious emblem. Around the sides of the lid are alternating sprays of peach and lingzhi fungus, which also offer wishes for long life. The finial on the lid is in the form of a lotus bud – a reference both to purity and to the Buddhist belief in rebirth through the lotus flower.

A small number of other jars of this type have been published, including one which was excavated in 1980 in the Chaoyang district of Beijing, and is now in the Capital Museum, Beijing (illustrated in Shoudu bowuguan cangci xuan, Beijing, 1991, pl. 121). Another is in the Hong Kong Museum of Art; a third, which was formerly in the collections of Charles Russell and Mrs. Ivy Clark, is now in the British Museum, London (illustrated by J. Harrison-Hall, Ming Ceramics in the British Museum, London, 2001, p. 238, no. 9:50. Further similar jars are in the collections of the Museum of Decorative Arts, Copenhagen (illustrated by D. Lion-Goldschmidt, La Porcelaine Ming, Fribourg, 1978, p. 134, no. 124); the Fengchengxian Museum, Jiangxi province (illustrated in Zhongguo wenwu jinghua da cidian, Shanghai, 1995, p. 393, no. 766); and the Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Tokyo (illustrated in Chinese Ceramics in the Idemitsu Collection, Tokyo, 1986, pl. 191. Smaller versions of this jar type are also known.

The current jar is exceptional for its size, the quality of the cobalt used in its decoration, its condition, and the fact that it has retained its lid. Most remarkable is the fine quality its lively decoration. This vessel also reflects an important aspect of Chinese traditional culture, and particularly the interests and preoccupations of the Jiajing Emperor himself.

Christie's. Important Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art, Hong Kong, 27 November 2019

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F73%2F65%2F119589%2F126877960_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F34%2F60%2F119589%2F126529723_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F76%2F09%2F119589%2F122485126_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F80%2F25%2F119589%2F122457923.jpg)