Imperial Chinese 'immortals' screen for sale at Bonhams in London

LONDON - An extraordinary Imperial Chinese twelve-leaf screen comprising 64 magnificent porcelain panels depicting tales from Chinese mythology which may have graced an Imperial throne room, will be sold at Bonhams Fine Chinese Art sale in London on May 15.

It is estimated to sell for £800,000 to £1.2m. The immortals are characters from Chinese mythology who symbolize good fortune and longevity.

In the Imperial halls, such screens were often used as backdrops to thrones, reinforcing the Imperial eminence and stature behind the throne. No cost was spared in their production, using precious materials generously, such as zitan and huanghuali woods, cinnabar lacquer, gilt on black lacquer and embellishments with porcelain panels, hardstones, and cloisonné and painted enamels.

The Imperial very rare famille rose and huanghuali twelve-leaf screen is dated to the Jiaqing reign period (1796-1820).

The Qianlong Emperor abdicated his throne in 1796 out of filial respect to his grandfather the Kangxi Emperor, but continued ruling in effect until his death in 1799. Therefore, the Imperial taste and demand as well as the zenith of craftsmanship achieved during the Qianlong period (1736-1795), continued well into the subsequent Jiaqing period (1796-1820). The present screen can be ascribed to this group with its peerless quality combining two mediums, huanghuali wood and porcelain panels, attaining an imposing and opulent effect imbued with symbolism.

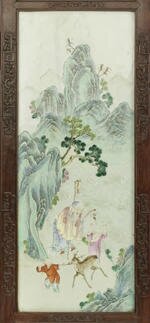

Each of the twelve leaves is finely carved from huanghuali, framing the porcelain plaques and set within the massive tiered huanghuali dais. Huanghuali wood, one of the most luxurious close-grained sub-tropical hardwood timbers used from the Ming dynasty onwards, was highly sought after for its rich yellow-hued grain.

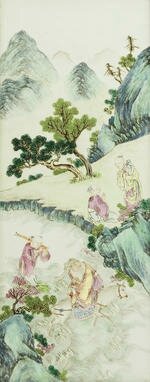

The twelve leaves of the screen are resplendently inset with 64 famille rose porcelain plaques. These are superbly enamelled with mythical imagery of Daoist Immortals, auspicious flowers and birds, laden with puns, rebuses and symbolic significance.

Asaph Hyman, Director of Chinese Art, commented: "The rare screen is a statement of Chinese Imperial art at its zenith demonstrating Qing dynasty master-craftsmanship. As it was made for a Qing Palace, no cost was spared in its production making use of the finest materials and artisan skills".

An Imperial very rare famille rose and huanghuali twelve-leaf screen, Jiaqing. Estimate £800,000 - 1.2 million (€970,000 - 1.5 million). Photo Bonhams

The large huanghuali-framed screen inset with twelve leaves, each enclosing five famille rose porcelain plaques, all raised upon an imposing tiered huanghali dais flanked by openwork huanghuali terminals; the main famille rose panels superbly enamelled with groups of Immortals, each with his attribute, engaged in various pursuits in a mountainous river landscape with trees, flowers and bamboo; the smaller rectangular top and bottom famille rose panels colourfully decorated with a bat above a cluster of peaches above a leafy lotus blossom, each such panel framed by a lotus scroll on a turquoise ground; each leaf with two further famille rose panels between the main plaque and the lowest one, with each smaller rectangular panel decorated with a pair of confronted chi dragons clawing at a foliate lotus blossom and pursuing the flaming pearl of wisdom, each such panel framed by a lotus scroll on pink ground, and the square famille rose plaques each finely enamelled with a flower and a pair of birds representing the twelve months, the huanghuali framed leaves finely carved in relief with interlocking archaistic scrolls, above an openwork section carved with a foliate lotus blossom, the flanking reticulated terminals carved with foliate scrolls interlocked with archaistic geometric scrolls, all raised on the impressive tiered pedestal, carved in relief with double and single rows of lotus petal panels above and below the waisted section, with each petal superbly carved with a lotus blossom below a ruyi, all further supported on short feet. Overall 383cm (150in 3/4) wide x 175cm (68 7/8in) high (18).

Provenance: according to the family acquired in the 1970s from an important Italian family prominent in industry.

Accompanied by a certificate from CNR-IVALSA, National Research Council of Italy, Trees and Timber Institute, no.0004214, dated 2 December 2013, certifying that the wood is of the genus Dalbergia sp., of the family Leguminosae Papilionaceae.

The Qianlong Emperor, though abdicating his throne in 1796 out of filial respect to his grandfather the Kangxi Emperor, continued ruling in effect until his death in 1799. Therefore, the Imperial taste and demand as well as the zenith of craftsmanship achieved during the Qianlong period, continued well into the Jiaqing period. The present screen can be ascribed to this group with its peerless quality combining two mediums, huanghuali wood and porcelain production, to attain an imposing and opulent effect imbued with symbolism.

Panel 5: The fifth panel depicts the Immortal Li Tieguai performing a miracle of healing and feeding the old and the sick. In the distance a sage is observing a bat. The Chinese character for bat is fu 蝠, which is a homophone with fu 福 or good fortune. Li Tieguai, also known as Iron Crutch Li, was originally a handsome and healthy man, who in trying to achieve Immortality, left his body to meet temporarily with other Immortals in heaven. Li asked his disciple to look after his body for seven days while he was gone. If he did not return within seven days, his disciple was instructed to cremate the body, as he was told he might already have become an Immortal. Unfortunately for Li, his disciple six and a half days later had to return to his dying mother, and so cremated Li's body. When Li returned though, he discovered the only body he could reincarnate into was that of a lame beggar who died in a ditch. And so, Li's spirit entered the beggar's body and he took on the appearance of an ugly old man with dirty face, scraggy beard, and messy hair, aided in walking with an iron crutch. Li was benevolent to the poor, sick and needy, and would dispense endless medicine from his magical gourd, which would also be his residence at night.

Panel 6: The sixth panel would appear to depict three Immortals: Lu Dongbin riding on a cloud with his fly whisk representing the spiritual power of the Immortal to whisk away the problems of the world; Shoulao with his gnarled staff suspending a double-gourd and holding a peach; and possibly Zhang Guolao.

Panel 7: The seventh panel depicts the 'seven daughters of the Jade Emperor' who travelled to the mortal world. The youngest of the seven maidens was in search of her lost weaving tools and the 'feather coat' (without which she was unable to fly back to Heaven). Another version of story states that the seventh fairy's flying 'feather coat' was taken by a mortal named Dong Yong. The maiden fell in love with Dong Yong, a cowherd who had sold himself into servitude to pay for his father's funeral. With the help of the other fairies, she manages to weave ten pieces of brocade for Dong Yong to pay off his debt. Before they can begin their life together, the Jade Emperor orders his daughters to return home, allowing the couple to reunite only once a year at the 七夕 (the 7th evening) - later known as the traditional Chinese Qixi Festival across the Milky Way.

Panel 8: The eighth panel depicts the Immortal Zhang Guolao riding his donkey across the river, while an attendant carries for him his 'fish drum', a bamboo cylindrical tube that carried iron mallets dispelling evil. Zhang Guolao is said to have been fond of making wine from herbs and shrubs that would have healing and medicinal properties. In the background, an attendant brings a jar of Zhang's medicinal wine to a seated sage.

Panel 9: The theme of the ninth panel is money and wealth. Zhongli Quan with fan in hand is standing on Hai's mythical three-legged toad. Liu Hai is borne by the vapour emanating from the toad, coaxing it with a string of gold coins. Behind Zhongli Quan is the androgynous Immortal Lan Caihe with bamboo flower basket and gardening hoe standing atop a fish. Zhongli Quan was said to be able to transform rocks into silver and gold to help the poor. The symbol of wealth, Liu Hai, according to legend coaxed a three-legged toad out from harming a village with his poisonous vapours by feeding it the coins. Lan Caihe is often regarded as a minstrel, talented in music who after drawing mesmerized crowds around him would earn gold coins; so many in fact, that as he walked, gold coins would fall to the ground for the poor to collect. In the far distance, Shoulao carries branches of peaches, symbols of longevity.

Panel 10: The tenth panel depicts a young boy held by a man, possibly the Star God Fu, the God of good fortune, reaching out to hold a ruyi sceptre held by the Star God Lu, thus representing the wish for attainment of good fortune, prosperity, rank and influence. In the background are two male figures, with one writing on the rock face.

Panel 11: The eleventh panel depicts the immortal Han Xiang playing his life-giving flute while crossing the sea on the back of a crab as he journeys to attend the banquet of Immortal peaches. In the background, deep in the mountains, are the Hehe Erxian, symbolising harmony and union.

Panel 12: The twelfth panel depicts the Daoist Celestial Master Zhang Daoliang with his tiger. Zhang wears the robes of a high-ranking scholar official, but he wished to become a hermit recluse and refused to enter government service. Legend has it that one day, a deified Laozi warned Zhang Daoliang that plagues, beasts, and the demons of the underworld were due to be released upon humankind, and that only some would be chosen as survivors as 'seed people' to repopulate the new age of Great Peace. Zhang Daoliang then endeavoured to reform degenerate practices and began advocating longevity practices. The tiger beside him is a reminder of the beasts that will soon ravage mankind.

16 Floral panels: Twelve square and four rectangular panels are finely enamelled with a variety of floral sprays, each decorated with a pair of birds. The blossoms include, peony, lotus, chrysanthemum, camellia, prunus, apricot, poppy, rose, morning glory, wintersweet, aster, and nandina as well as lingzhi fungus and bamboo and the birds include quails, pheasants and magpies.

The flowers are probably a symbolic representation of the twelve months but are further imbued with other layers of meanings. A pair of magpies conveys the wish for a happy marriage; the bamboo represents the highest Confucian ideal of perseverance and moral integrity for its uprightness, and unbending nature; the peony, symbol of royalty and virtue, is also called the 'flower of wealth and honour 富貴花'; the long-tailed birds, known as 'shoudainiao 綬帶鳥' of which the 'shou 綬' sounds the same as longevity, 'shou 壽' and thus carries this wish; the two quails, 'anchun 鵪鶉', amidst chrysanthemums 'juhua 菊花' mean 'may you dwell in peace and be content with your work' (an ju le ye 安居樂業); long-tailed birds and camellia 'chahua 茶花' represent the wish for longevity as the camellia is the flower of spring, a symbol of eternal youth, whilst the birds stands for longevity; and the lotus, pronounced 'he' is associated with the Immortals Hehe Erxian and is one of the Eight Buddhist Emblems.

Further symbolism is represented by the top and bottom panels each enamelled with a bat suspending a cluster of peach above a lotus blossom. These symbolise the wish for blessings and longevity whilst the lotus, one of the Eight Buddhist Emblems, also representative of purity. The set of panels decorated with a pair of confronted chi dragons, pursuing the flaming pearl of wisdom, associates the dragon with knowledge and supernatural powers.

Compare a related twelve-leaf 'famille rose' porcelain and hardwood screen, Jiaqing/ Daoguang, which was sold at Sotheby's New York on 30 March 2006, lot 190.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F91%2F48%2F119589%2F128923043_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F84%2F09%2F119589%2F128922928_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F74%2F57%2F119589%2F128709421_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F96%2F72%2F119589%2F128683141_o.jpg)