"The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture, 1600–1700" @ National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Attributed to Juan Martínez Montañés, Immaculate Conception (la Purisma), about 1628, polychromed wood; overall: 144 x 49 x 53 cm (56 11/16 x 19 5/16 x 20 7/8 in.); base: 37.5 x 97.5 x 58.5 cm (14 3/4 x 38 3/8 x 23 1/16 in.). Church of the Anunciación, Seville University © Photo Imagen M.A.S. Reproduction courtesy of Universidad de Seville

Washington, DC—Masterpieces created to shock the senses and stir the soul are spotlighted in The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture, 1600–1700, on view at the exhibition's only U.S. venue―the National Gallery of Art―from February 28 through May 31, 2010. This landmark reappraisal of religious art from the Spanish Golden Age includes 11 paintings by Diego Velázquez, Francisco de Zurbarán, and others, displayed for the very first time alongside 11 of Spain's remarkable polychromed (painted) sculptures, many of which have never before left Spain and are still passionately venerated across the Iberian Peninsula in monasteries, churches, and processions.

During the Spanish Counter-Reformation, religious patrons, particularly the Dominican, Carthusian and Franciscan orders, challenged painters and sculptors to bring the sacred to life, to inspire both devotion and emulation of the saints. The exhibition brings together some of the finest depictions of key Christian themes including the Passion of Christ, the Immaculate Conception and the portrayal of saints, notably Pedro de Mena's austere Saint Francis Standing in Ecstasy (1663), which has never before left the sacristy of Toledo cathedral.

By installing polychromed sculptures and paintings side by side, the exhibition shows how the hyperrealistic approach of painters such as Velázquez and Zurbarán was clearly informed by the artists' familiarity―and in some cases direct involvement―with sculpture. During this period, sculptors worked very closely with painters, who were taught the art of polychroming sculpture as a part of their training.

The Sacred Made Real is organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and the National Gallery, London, where it was on view from October 21, 2009, through January 24, 2010.

"We hope that this exhibition will convey the artistic excellence and spiritual profundity of Spanish baroque art to our visitors," said Earl A. Powell III. "We are grateful to the museums and Spanish ecclesiastical institutions that have agreed to lend these exceptional works, which together provide an illuminating and powerful experience."

Exhibition Support

The exhibition in Washington is made possible by the generous support of Robert H. Smith, The Charles Engelhard Foundation, and an anonymous donor.

The exhibition is presented on the occasion of the Spanish Presidency of the European Union, with the support of the Ministry of Culture of Spain, the Spain–USA Foundation and the Embassy of Spain in Washington, DC. This exhibition is included in the Preview Spain: Arts & Culture '10 program.

Additional support for the Washington presentation is provided by Buffy and William Cafritz.

The exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

Exhibition Background

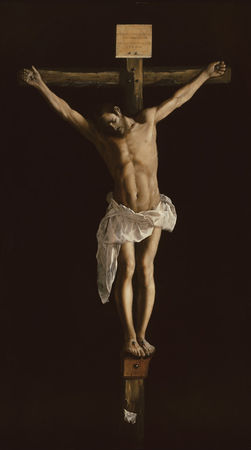

A crucial loan to the exhibition, Zurbarán's masterpiece The Crucifixion (1627) from the Art Institute of Chicago achieves an astonishing sculptural illusion on canvas. When seen in close proximity to Juan Martínez Montañés' polychromed sculpture of 1617 from the Church of the Convent of Santo Ángel, Seville, these two art forms begin an intense natural dialogue.

In Seville, Francisco Pacheco taught a generation of artists, including Velázquez (later his son-in-law), the skill of painting sculpture as an integral element of their training. Pacheco himself painted the flesh tones of superb wooden sculptures carved by fellow Andalucian artist Montañés, known by his contemporaries as "the god of wood." Among the most important examples of their collaboration is their life-size Saint Francis Borgia (1624) from the Church of the Anunciación, Seville University, commissioned by the Jesuits to celebrate Borgia's beatification that year. Another highlight of the exhibition is the fascinating juxtaposition of Velázquez's The Immaculate Conception (1618–1619) from the National Gallery, London, with Montañés' exquisite polychrome sculpture of the same subject (c. 1628) from the Church of the Anunciación, Seville University.

To obtain even greater realism, some sculptors such as Pedro de Mena and Gregorio Fernández introduced glass eyes and tears, as well as ivory teeth, into their sculptures. In one of Mena's most proficient works, Mary Magdalene Meditating on the Crucifixion (late 1660s), the artist used several strands of twisted wicker for his subject's long flowing hair and animal horn for her toenails.

Throughout Semana Santa (Holy Week) in Spain, some 17th-century polychrome sculptures are still carried through the streets by religious confraternities, particularly in Seville, Granada, and Valladolid—the most important centers of this art. One such processional sculpture included in the exhibition is the Pietà (c. 1680–1700) from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

During the evening of Palm Sunday, Seville's Archicofradía del SantÍsimo Cristo del Amor (Confraternity of the Christ of Love) process a life-size sculpture Christ on the Cross by Juan de Mesa. The exhibition features a smaller version of this work (c. 1621), which although non-processional, plays a vital role in the pastoral life of the confraternity.

Zurbarán's heightened illusionism shows an acute understanding and appreciation of sculpture, as seen in the brilliant handling of drapery in his painting, Saint Serapion (1628) from the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, CT, which is among the artist's greatest achievements. The saint's luminous white habit cascades with astonishingly rendered folds of deep shadow. Here, Zurbarán demonstrates that painting can indeed achieve the same disconcerting realism as sculpture.

The religious art of 17th-century Spain pursued a quest for realism with uncompromising zeal and genius. Painting and sculpture are distinct arts, but The Sacred Made Real shows how, in 17th-century Spain, they were drawn together in the service of ardent devotion and the quest to appeal to religious sensibilities.

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), Portrait of Juan Martínez Montañés, 1635–1636, oil on canvas, 109 x 83.5 cm (42 15/16 x 32 7/8 in.), Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Juan de Mesa (1583–1627), Christ on the Cross (detail), about 1618–1620, polychromed wood, 100 x 65 x 22 cm (39 3/8 x 25 9/16 x 8 11/16 in.), Archicofradía del Santísimo Cristo del Amor, Collegiate Church of El Salvador, Seville © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Juan de Mesa (1583–1627), Christ on the Cross, about 1618–1620, polychromed wood, 100 x 65 x 22 cm (39 3/8 x 25 9/16 x 8 11/16 in.), Archicofradía del Santísimo Cristo del Amor, Collegiate Church of El Salvador, Seville © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), Saint Luke Contemplating the Crucifixion, 1630s, oil on canvas, 105 x 89 cm (41 5/16 x 35 1/16 in.), Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Francisco Antonio Gijón (1653–c. 1721) and unknown painter (possibly Domingo Mejías), Saint John of the Cross (detail), c. 1675, painted and gilded wood, 168 cm (66 1/8 in.), National Gallery of Art, Washington, Patrons' Permanent Fund © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Attributed to Juan Martínez Montañés (1568–1649) and unknown painter, The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (detail), c. 1628, painted and gilded wood, 144 x 49 x 53 cm (56 11/16 x 19 5/16 x 20 7/8 in.), Church of the Anunciación, Seville University © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Attributed to Juan Martínez Montañés (1568–1649) and unknown painter, The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception, c. 1628, painted and gilded wood, 144 x 49 x 53 cm (56 11/16 x 19 5/16 x 20 7/8 in.), Church of the Anunciación, Seville University © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), The Immaculate Conception, 1618–1619, oil on canvas, 135 x 101.6 cm (53 1/8 x 40 in.), The National Gallery, London, Bought with the aid of The Art Fund, 1974 © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Juan Martínez Montañés (1568–1649) and Francisco Pacheco (1564–1644), Saint Francis Borgia (detail), c. 1624, painted wood and cloth stiffened with glue size, 174 x 68 x 51 cm (68 1/2 x 26 3/4 x 20 1/16 in.), Church of the Anunciación, Seville University © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Juan Martínez Montañés (1568–1649) and Francisco Pacheco (1564–1644), Saint Ignatius Loyola, 1610, painted wood and cloth stiffened with glue size, 173.5 x 70 x 55 cm (68 5/16 x 27 9/16 x 21 5/8 in.), Church of the Anunciación, Seville University © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Alonso Cano (1601–1667), Saint Francis Borgia, 1624, oil on canvas, 186 x 120 cm (73 1/4 x 47 1/4 in.), Museo de Bellas Artes, Seville © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Juan Martínez Montañés (1568–1649) and Francisco Pacheco (1564–1644), Saint Francis Borgia, c. 1624, painted wood and cloth stiffened with glue size, 174 x 68 x 51 cm (68 1/2 x 26 3/4 x 20 1/16 in.), Church of the Anunciación, Seville University © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Pedro de Mena (1628–1688), Saint Francis Standing in Ecstasy (detail), 1663, painted wood, glass, cord, and human hair, 97 x 33 x 31 cm (38 3/16 x 13 x 12 3/16 in.), Cabildo de la Santa Iglesia Catedral Primada, Toledo © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Pedro de Mena (1628–1688), Saint Francis Standing in Ecstasy, 1663, painted wood, glass, cord, and human hair, 97 x 33 x 31 cm (38 3/16 x 13 x 12 3/16 in.), Cabildo de la Santa Iglesia Catedral Primada, Toledo © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Pedro de Mena (1628–1688), Christ as the Man of Sorrows (Ecce Homo) (detail), painted wood, human hair, ivory, and glass, 98 x 50 x 41 cm (38 9/16 x 19 11/16 x 16 1/8 in.), Real Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales, Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Pedro de Mena (1628–1688), Christ as the Man of Sorrows (Ecce Homo), painted wood, human hair, ivory, and glass, 98 x 50 x 41 cm (38 9/16 x 19 11/16 x 16 1/8 in.), Real Monasterio de las Descalzas Reales, Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Gregorio Fernández (1576–1636) and unknown painter, Ecce Homo, before 1621, painted wood, glass, and cloth, 182 x 55 x 38 cm (71 5/8 x 21 5/8 x 14 15/16 in.), Museo Diocesano y Catedralicio, Valladolid © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660), Christ after the Flagellation Contemplated by the Christian Soul, probably 1628–1629, oil on canvas, 165.1 x 206.4 cm (65 x 81 1/4 in.), The National Gallery, London, Presented by John Savile Lumley (later Baron Savile), 1883 © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Juan Martínez Montañés (1568–1649) and unknown painter, Christ on the Cross (Cristo de los Desamparados), 1617, painted wood, 350 x 200 x 57.5 cm (137 13/16 x 78 3/4 x 22 5/8 in.), Church of the Convent of Santo Ángel, Carmelitas Descalzos, Seville © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), Christ on the Cross, 1627, oil on canvas, 291 x 165 cm (114 9/16 x 64 15/16 in.), The Art Institute of Chicago, Robert A. Waller Memorial Fund 1954.15 © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Reconstruction of the original setting of Zurbarán’s Christ on the Cross, photograph © Robert Cripps © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

After Pedro de Mena (1628–1688), Mary Magdalene Meditating on the Crucifixion, late 1660s, painted cedar, glass, and horn (for fingernails), 64 3/16 in. (163 cm), Church of San Miguel, Valladolid © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Jusepe de Ribera (1591–1652), The Lamentation over the Dead Christ, early 1620s, 1946, oil on canvas, 129.5 x 181 cm (51 x 71 1/4 in.), The National Gallery, London, Presented by David Barclay, 1853 © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Francisco Ribalta (1565–1628), Christ Embracing Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, c. 1624–1627, oil on canvas, 158 x 113 cm (62 3/16 x 44 1/2 in.), Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

Francisco de Zurbarán (1598–1664), Saint Serapion, 1628, oil on canvas, 120.8 x 104.1 cm (47 9/16 x 41 in.), Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, The Ella Gallup Sumner and Mary Catlin Sumner Collection Fund © 2010 National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F54%2F46%2F119589%2F119205652_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F98%2F13%2F119589%2F112775955_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F22%2F02%2F119589%2F111454616_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F65%2F28%2F119589%2F69576540_o.jpg)