"C'est la vie, Vanités de Caravage à Damien Hirst" @ Fondation Dina Vierny - Musée Maillol

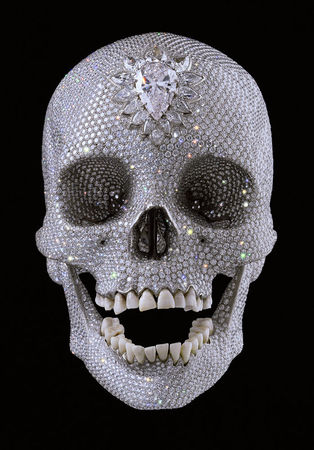

Damien Hirst, The Love for God, Laugh 2007. (c) Damien Hirst. All rights reserved, Adagp, 2009.

"C'est la vie ! Vanités de Caravage à Damien Hirst" présente environ 160 œuvres, peintures, sculptures, photographies, vidéos, bijoux, objets.

Le crâne en diamants de Damien Hirst, première icône du XXIe siècle, est symptomatique du regain d'intérêt pour les Vanités qui s'introduisent dans le domaine de l'art contemporain et s'affichent partout: livres, pochettes de disques, design, bijoux...

Métaphore de l'émiettement spirituel et de l'éclatement du monde, d'une planète mondialisée en proie à la menace écologique, impuissante à contenir le bouillonnement qu'elle emprisonne, parabole de la désacralisation de la vie et de la mort dans les sociétés occidentales, cette omniprésence de la Vanité, cristallise le vide de sens d'une civilisation qui s'égare dans sa soif de contrôle. Notre société du spectacle reprend l'iconographie de la tête de mort, utilisée dès 1948 par les «Hell's Angels», ce gang de motards de la côte Ouest des Etats-Unis, qui détournait ces images à des fins contestataires et anarchistes. La contre-culture est devenue culture.

Même si ce thème n'a jamais cessé de hanter, de fasciner, d'interroger... des mosaïstes de Pompéi aux graveurs des danses macabres médiévales, des peintres de Vanités du XVIIe siècle aux surréalistes du XXe, des artistes du néo-Pop Art aux agents provocateurs de l'art le plus récent. Débutant par ce foisonnement des vanités dans l'art contemporain et remontant le fil du temps, à travers des œuvres peu montrées, voire cachées par des collectionneurs célèbres, l'exposition propose un parcours singulier dans histoire de l'art. Elle dépasse les clichés morbides attachés à la représentation de la mort, au profit d'un hymne à la vie, d'une philosophie allègre, une tentative ultime pour repousser les limites de la vie.

"Tête de mort II" de Niki de Saint Phalle (1988). Polyester peint (115 x 125 x 90 cm). Collection particulière. lepoint.fr © Galerie JGM / 2009 Niki Charitable Art Foundation / Adagp, Paris 2010

Niki de Saint Phalle, Tête de mort II, 1988 Crédit : SIPA

Xavier Veilhan, Crâne (version orange) Crédit : SIPA

Erik Dietman, La Sainte famille à poil, vers 1990. Crânes, fémurs et fer, socle en bois, capot en verre (48 x 85 x 53 cm). Collection particulière. Crédit : D.R. / Adagp, Paris 2010

Memento Mori (Death comes to the dinner table), de Giovanni Martinelli (vers 1635). Huile sur toile (114,2 x 158 cm). Galerie G. Sarti, Paris. lepoint.fr © Gilles de Fayet, France

Christian Boltanski, Théâtre d'ombres. Crédit : SIPA

Annette Messager, Gants-tête, 1999, collection AM et M Robelin © Adagp, Paris 2009

Memento mori, mosaïque polychrome de Pompéi, Ier siècle, Musée national d'archéologie de Naples © Archives surintendance spéciale Beni et archologici Naples et Pompei

Mosaïque polychrome de Pompéi , de Memento Mori (Ier siècle). Base calcaire et marbres colorés (41 x 47 cm). Musée national. lepoint.fr © Archives surintendance spéciale Beni et d'archéologie de Naples

Crédit SIPA

PARIS.- Olivier Lorquin, president of the Fondation Dina Vierny – Musée Maillol, in October 2009 appointed Patrizia Nitti as art director of the institution.

The first exhibition to be curated by her is « C’est la vie ! – Vanités de Caravage à Damien Hirst » ( That’s Life ! – Vanities from Caravaggio to Damien Hirst). It will present about 160 works : paintings, sculptures, photographs, videos, jewelry, objects…

Damien Hirst’s diamond encrusted skull, the first icon of the 21st century is symptomatic of the resurgence of interest in the Vanities, brought into the contemporary art world and seen everywhere: books, record covers, design, jewels…

As a metaphor of the spiritual splintering and of the world’s break-up, of a globalized planet prey to the ecological menace, powerless to contain the ferment of ideas it curtails, a parable of the desacralisation of life and death in Western societies, this omnipresence of Vanity, crystallizes the lack of meaning of a civilization floundering amidst its thirst for control. Our spectator society is renewing with the death’s head, used as early as 1948 by the « Hell’s Angels », that gang of bikers on the Western Coast of the USA, who re-used those images with an aim to protest and anarchy. Counter-culture has become culture.

Even if this theme never ceased to haunt, fascinate, and be a cause for reflection from the mosaicists in Pompey to the engravers of medieval death’s dances, from the painters of Vanities in the 17th century up to the 20th century Surrealists, from neo-Pop Artists until the most recent agents provocateurs of the latest art forms.

Starting with this flamboyance of vanities in contemporary art and going backwards in time, by means of little shown works, even those hidden by famous collectors, the exhibition provides an unusual approach to art history.

It goes well beyond the morbid clichés attached to representations of death, to favor a hymn to life, a joyful philosophy, a final attempt to push back the limits of life.

The Elders’ “Tempus fugit”

We know that in Neolithic times the skull was worshipped, since the discovery of a skull with eyes whitened by chalk in Jericho, that dates back to 7000 years BC. And although it would be foolhardy to date the appearance of such a basic form as that of a dead body, it seems as though it was the Greeks, in Hellenistic times, who were the first in the West, to suddenly dare to represent the skeleton in order to invoke the passage of time and life’s brevity. That is what we find in Virgil’s “Tempus fugit” and in the striking Roman mosaics in Pompey, shown here.

But it was at the end of the Middle Ages, in the 14th and 15th centuries, that the skeletons’ dance of death was invented, as well as the “memento mori”, in which the skull with its unhinged mouth is glimpsed behind the portrait of the deceased! The horrors of the Black Death, combined with the Hundred Years’ War and the new Christian theology of the “Drama of agony” brought horrible death into the field of art. After being collective, death became individual. For a while the Renaissance put a halt to that macabre carnival. But the 17th century re-awakened that celebration in all its violence. With Caravaggio as first witness, who linked his invention of chiaroscuro in the Roman dens of iniquity to a morbid realism. His “Saint Francis”, like, later on, those of Georges de la Tour in France or of Francisco de Zurbaran in Spain, emphasized more strongly the skull in the saint’s hand than the man’s own face, left in shadows.

With the arrival of Still-lifes and, more specifically, the Vanities in Holland at the same time, death took over paintings.

Pietro Paolini slipped a skull into his “Saint Jerome meditating” and Genovesino surrounded a death’s head with the body of a sleeping putto. Nineteenth century Puritanism did not much favor those outpourings, and it took Théodore Gericault, seeking inspiration for his “Radeau de la Méduse”, to paint “Les trois Crânes” as a kind of new Trinity, or the angry Paul Cézanne who brought the genre back into favor when he painted pyramids of skulls in his studio.

The moderns’ “God is Dead!”

Positivism and the industrial age, which saw itself as immersed in progress, thought it had finished with death’s victory.

But the Great War of 1914 recalled all of its pertinence. During the thirties, facing the increase in perils, Pablo Picasso re-found Zurbaran’s inspiration when painting skulls like so many allegories of the modern world. Georges Braque in his “Atelier au crâne”, as though stimulated by “Guernica”, followed suit. As would, much later on, the Catalan Miguel Barceló when he went on to paint skulls in the Mali desert. But the massacres during World War Two and the appalled discovery of the Shoah’s death camps, turned the artists’ attention away from those overwhelming representations! – death was once again collective.

The contemporary artists’ “Who gives a damn about death!”

Post-war, neither abstraction nor its opposite Pop Art – which glorified the consumer society, wanted to renew with the art of death. Andy Warhol however, in the seventies, undertook a series of pink and green skulls. Thus we can understand his collaboration with Jean-Michel Basquiat during the eighties, around the voodoo-type charms of that Black Picasso. In reply to Basquiat’s black magical graffiti came the white magic of Keith Haring’s sinewy strokes.

In Germany, after the very Caravaggio-like vanities of Gerhard Richter, the New Wild painted the Aids years: Georg Baselitz, A.R.Penck and Markus Lüpertz leading the way. Those years are to be found again in Robert Mapplethorpe’s “Self portrait with a cane”. Death is ever present in the very real skulls painted by the Mexican Gabriel Orozco, in “Proposal for a posthumous portrait” by Douglas Gordon, the death’s heads covered in insects by Jan Fabre, or in Yan Pei Ming’s large grey skulls.

At the start of the 21st century, the representation of death has changed in nature.

All fear having been removed, the skull and the skeleton become a motif, a fashionable phenomenon. “Who gives a damn about death!” proclaimed the years 2000, when Marina Abramovic carried around a skeleton on her back, Cindy Sherman covered a skull in flowers, the Chapman brothers personified “Migraine” by means of a rotting Frankenstein’s head.

Does death become us so well?

Le Caravage, Saint François en méditation, vers 1602 © Private collection courtesy of Whitfield Fine Art, London

"Saint François en méditation" de Caravage (vers 1602). Huile sur toile (36,5 x 91,5 cm). lepoint.fr © Private collection courtesy of Whitfield Fine Art, London

Francisco de Zurbaran, San Francisco arrodillado (Saint François agenouillé), vers 1635. Crédit : Collection Adolfo Nobili, Milan

Luigi Miradori (dit Genovesino), Cupidon endormi, vers 1652, Museo civico Ala Ponzone, Cremona © Sistema Museale della Città di Cremona - Museo civico Ala Ponzone, Cremona

Cupidon endormi, de Luigi Miradori (dit Genovesino) (vers 1652). Huile sur toile (76 x 61 cm). Museo civico Ala Ponzone, Cremona. lepoint.fr © Sistema Museale della Città di Crem

Théodore Géricault, Les trois crânes, 1812-1814. Crédit : Jacques Faujour

"Les Trois Crânes" de Théodore Géricault (1812-1814). Huile sur toile (31,5 x 60 cm). Musée Girodet, Montargis. lepoint.fr © Jacques Faujour

Paul Cézanne, Nature morte, crâne et chandelier (c) Merzbacher Kunststiflung

Georges Braque, L'Atelier au crâne, 1938, collection particulière © Sotheby's / Adagp, Paris 2009

Andy Warhol, Skull, 1976. Crédit : Jean Alex Brunelle / The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visuals Arts, Inc. / Adagp, Paris 2010

Skull, d'Andy Warhol (1976). Sérigraphie et polimerie sur toile (38 x 48 cm). Courtesy Loïc Malle. lepoint.fr © Jean Alex Brunelle / The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visuals Arts, Inc. /A.A.S Paris

Michel Journiac, Rituel pour un mort, 15 decembre 1978, 1960. Crédit : Arphot / Jean Michalon, Paris, CNAP / Adagp, Paris 2010

Yan Pei Ming, Crâne, 2004. Crédit : Jean Alex Brunelle / Adagp, Paris 2010

Crâne, de Yan Pei-Ming (2004). Huile sur toile (150 x 150 cm). Collection particulière. lepoint.fr © Jean Alex Brunelle / Adagp, Paris 2010

Jan Fabre, L'Oisillon de Dieu, 2000, collection particulière © Adagp, Paris 2009

"L'Oisillon de Dieu" de Jan Fabre (2000). Crâne, ailes de coléoptères, perruche empaillée (30 x 25 x 20 cm). Collection particulière. lepoint.fr © Didier Michalet / Adagp, Paris 2010

Marina Abramovic, Carrying the skeleton I, 2008. Crédit : Adagp, Paris 2010

Carrying the skeleton I, de Marina Abramovic (2008). lepoint.fr © Adagp, Paris 2010

Marc Gassier, bague et anneau en ronde de squelettes, vers 1980. Crédit : Jean-Alex Brunelle / Galerie Yves Gastou

Jean-Michel Alberola, Rien, 1994. Néon et plexiglas (26 x 36 cm). Collection de l'artiste. © Courtesie Daniel Templon, Paris - Cliché B. Huet / Tutti, Adagp, Paris 2010

Nicolas Rubinstein, Sans titre, 2006. Crédit : Jean-Alex Brunelle

Philippe Pasqua, Crâne aux papillons. Crédit : Jean-Alex Brunelle / Adagp, Paris 2010

Bague "Alchimie" (modèle des années 1940). Or, émail blanc sur or, diamants, émail. Époque contemporaine. Collection particulière, courtesy Codognato. lepoint.fr © Andrea Melzi

"Vanité couronnée" (à partir de 1980). Or émaillé, cristal de roche. Collection particulière, courtesy Codognato. lepoint.fr © Andrea Melzi

Pendants d'oreilles "Nature morte" (Années 1950). Or, perles et diamants, émail. Collection particulière, courtesy Codognato. lepoint.fr © Andrea Melzi

"Crâne gaulois" de Serena Carone (1991). Technique mixte (18 x 12 x 12 cm). Collection Serge Bramly. lepoint.fr © Adagp, Paris 2010

Du 3 février au 28 juin 2010. Fondation Dina Vierny - Musée Maillol (Paris 7e). Tous les jours de 10h30 à 19h sauf les mardis, 11 euros.

Crédit : SIPA

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F99%2F61%2F119589%2F95805205_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F01%2F85%2F119589%2F94654854_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F51%2F78%2F119589%2F94654624_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F62%2F64%2F119589%2F94654191_o.jpg)